With a pandemic and all of its attendant human suffering, with economic devastation and so much loss of livelihood and dignity, with painful but overdue and much-needed conversations about structural and systematic racial injustice and inequity, and with so much division, disdain, and distrust, we need good leadership more than ever. Not because it is a cure-all, but because it is a prerequisite for stemming the crises, healing the wounds, and getting us moving in the right direction. Not just leadership at one level, but leadership at all levels of society and organizations. Not top-down, but leadership all around.

Yet too often we encounter not just mediocre but bad or even toxic leadership, the kind that not only fails to match the moment but that takes us in the wrong direction.

David Gergen, senior advisor to four U.S. presidents (from both parties), and author of Eyewitness to Power, wrote:

“Most books about leadership tell us what a person ought to do to become effective and powerful. Few tell us what to avoid. But the latter may be even more valuable because many people on the road to success are tripped up by their mistakes and weaknesses.”

No leader is perfect. We all have faults, flaws, blind spots, and shadow sides. But we have to understand and grapple with the problem of bad leadership if we are to figure out what kind of leadership is needed today and to develop the leaders needed for tomorrow.

Bad leadership comes in various degrees, starting with lacking desirable behaviors, moving to missing essential elements, and falling off a cliff when it comes to toxic leadership. We address each in turn below.

There are many things that can “derail” our leadership. We can:

- avoid difficult tasks

- be a bottleneck on decisions

- struggle with effective communication, listening, or delegation

- get caught up in firefighting—reacting to events without moving toward a worthy vision

- be too hard or too soft (what we call “steel and velvet” in our book, Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations)

- be overly rational and not sufficiently emotional, or vice versa

- be impulsive, insecure, or intimidating

- be overly optimistic or pessimistic

- be perfectionist, people pleasers, or procrastinators

There are many derailers, and most leaders have multiple derailers. Those willing to learn and develop and can turn to coaches, mentors, advisors, feedback, training, books, and more.

Some modern leadership frameworks can inform this discussion. Authentic leadership from Bill George incorporates purpose, values, commitment to relationships, self-discipline, and heart, and these in turn generate passion, connectedness, consistency, and compassion. It is easy to see how some leaders may struggle in some of these areas.

Relevant Leadership Frameworks

Servant leadership from Robert Greenleaf emphasizes that the leader’s essential role is to serve others—the team, the organization, the community, the nation, the world. At its best, servant leadership involves listening, empathy, persuasion, stewardship, commitment to people’s growth, and building community. Greenleaf wrote that its best test is this: “Do those served grow as persons; do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants?” Again, it is easy to see how many leaders might fall short in some or many of these areas.

Transformational leadership (from James MacGregor Burns, Bernard M. Bass, Bruce Avolio, and others) causes significant change in individuals and social systems. In contrast with transactional leadership, which focuses on exchanges of expediency between leaders and followers via contingent rewards, transformational leadership involves emotional influence, vision and inspirational motivation, stimulation of creativity and reflections on values and beliefs, and consideration of the needs of followers. Clearly, this is a high standard, and many leaders fall short of it.

Leadership scholars James Kouzes and Barry Posner, authors of the best-selling classic, The Leadership Challenge, have been surveying people around the world for decades on the “Characteristics of Admired Leaders.” More than 100,000 people worldwide have responded, and the findings are powerful and surprisingly consistent across nations: “for over three decades, there are only four qualities that have always received more than 60 percent of the votes… for the majority of people to follow someone willingly, they want a leader who they believe is

- Honest

- Competent

- Inspiring

- Forward-looking”

Clearly, leaders who lack honesty, competence, inspiration, and the ability to rise out of the present moment and look forward are not ones who will motivate and bring out the best in their followers. Honesty and credibility were far and away at the top of the list of things people want from their leaders:

“In every survey we’ve conducted, honesty is selected more often than any other leadership characteristic. Overall, it emerges as the single most important factor in the leader-constituent relationship…. First and foremost, people want a leader who is honest…. people want to follow leaders who, more than anything, are credible. Credibility is the foundation of leadership. People must be able, above all else, to believe in their leaders. To willingly follow them, people must believe that the leader’s word can be trusted, that they are personally passionate and enthusiastic about the work, and that they have the knowledge and skill to lead.” -James Kouzes and Barry Posner, The Leadership Challenge

What we want from leaders can be greatly influenced by the context. For example, during a crisis we want leaders who show humanity and grace under pressure; seek credible information from a diverse array of experts; form a brilliant crisis response team; communicate reality, urgency, and hope; make themselves present, visible, and available; maintain radical focus; make big decisions fast; empower leaders at all levels; restore psychological stability as well as financial stability; use purpose and values as a guide; create a sense that people are all in it together; build operating rhythm with small wins; maintain a long-term perspective; and anticipate and shape the “new normal.”

The Mega-Derailers

Bad leadership gets much worse in a hurry when leaders are deeply flawed with what I call mega-derailers. In my experience, ego and fear are the mega-derailers that are most pernicious, and that underly many of the other derailers. Cynicism, derision, and hate are also candidates for this list.

In her book, Multipliers, researcher and executive advisor Liz Wiseman notes that some leaders are “diminishers” who stifle others for their own benefit and aggrandizement, as opposed to “multipliers” who use their intelligence to amplify the smarts and capabilities of those around them. Diminishers include:

- Empire builders who hoard resources and underutilize talent

- Tyrants who create anxiety and suppress thinking

- Know-it-alls who showcase their own knowledge and tell people what to do

- Decision makers who make abrupt decisions that confuse people through the attendant chaos

- Micromanagers who take over and control things without trusting others to do their work

Importantly, Wiseman notes that there are also “accidental diminishers” who unintentionally shut down the intelligence and potential of others, for example by making others dependent on them by always rescuing them, overwhelming others with a flurry of ideas, consuming all the energy in the room, driving so hard or fast that others become passive spectators, or being so optimistic that others wonder if they appreciate struggles and risks.

Another version of bad leadership takes the benefits of transformational leadership noted above and twists it into pseudo-transformational leadership, which is characterized by self-serving yet inspirational leadership behaviors, discouraging independent thought in followers, and little caring for them. According to leadership scholars Bernard Bass and Ron Riggio, pseudo-transformational leaders are self-consumed, exploitative, and power-oriented, with warped moral values.

Recently, there has been increasing attention given to the “dark side of leadership,” often focused on narcissism (excessive need for admiration, disregard for others’ feelings, inability to handle criticism, and sense of entitlement), hubris (foolish pride or dangerous overconfidence), and exploitation (taking unfair advantage). To those we can add the scourges of bullying and harassment. And of course there is a long history of authoritarian and autocratic leadership, and unethical and criminal leadership.

Toxic leadership, according to Jean Lipman-Blumen of Claremont Graduate University and author of The Allure of Toxic Leaders, is “a process in which leaders, by dint of their destructive behavior and/or dysfunctional personal characteristics, inflict serious and enduring harm on their followers, their organizations, and non-followers, alike.”

Clearly, there is a range of bad leadership behaviors, ranging from mild to severe, but the important question remains as to why people continue to follow bad or toxic leaders.

Toxic Triangle

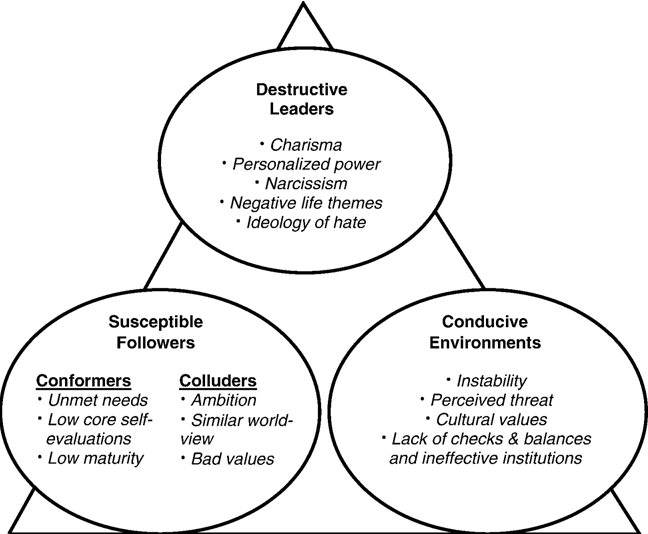

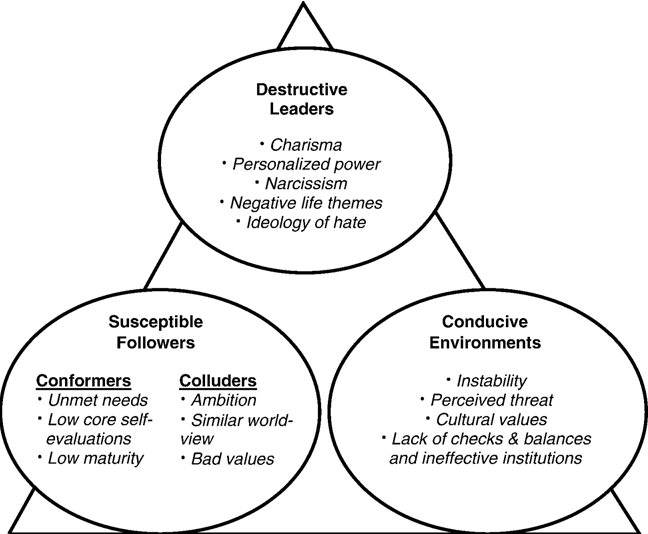

Some scholars have written about a “toxic triangle,” a confluence of leader, follower, and environmental factors that facilitate destructive patterns:

- Toxic leaders: charisma, narcissism, power, negative life themes and ideology

- Susceptible followers: unmet needs, low self-evaluation, ambition, similar world view

- Conducive environments: instability, perceived threats, lack of effective institutions and checks and balances

For years, many have pointed to the allure of charisma (compelling attractiveness or charm that can inspire devotion in others) and charismatic leadership, with people seduced by leader characteristics such as wealth, power, or confidence. We can also look at the “psychodynamics of leadership,” including the psychological underpinnings of leaders’ behavior. Harvard’s Joseph S. Nye, Jr.wrote in his book, The Powers to Lead, “People persist in looking for heroic leaders.” Abraham Zaleznik, a leading scholar in this field, asks, “Is the leadership mystique merely a holdover from our childhood—from a sense of dependency and a longing for good and heroic parents?” Many people just long for somebody to come along and fix things, abdicating their own agency and responsibility, and they believe it when some leaders make unrealistic promises.

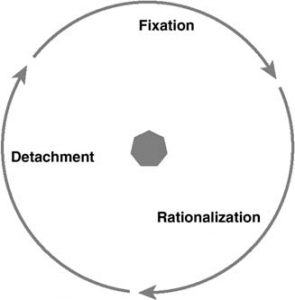

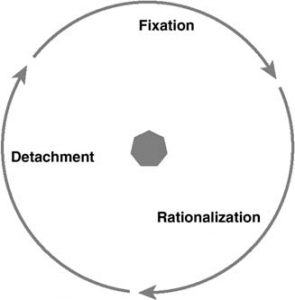

Ethics scholar Kenneth Goodpaster has done important work that I believe may shed light here. He notes that many leaders and followers get caught up in “teleopathy,” an unbalanced pursuit of purpose (e.g., winning in politics or sports, being a market leader in business, launching a space shuttle by X date), which is driven by fixation on set goals, rationalization of questionable behavior and decisions (e.g., everybody is doing it), and detachment from our personal values as we pursue those aims. I wonder if people are willing to stick with bad or unethical leaders because they are so caught up in winning and will do whatever it takes to prevail.

Our brains (and evolutionary biology) may also be part of the story. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt writes in his book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion:

“People bind themselves into political teams that share moral narratives. Once they accept a particular narrative, they become blind to alternative moral worlds…. If you think about moral reasoning as a skill we humans evolved to further our social agendas—to justify our own actions and to defend the teams we belong to—then things will make a lot more sense.”

Our brains have evolved to seek and defend tribes, and to be exceptionally good at rationalizing the behaviors and decisions of our tribe (and its leader), a phenomenon that is often unconscious (so exceptionally difficult to defend against).

As we can see, there are many reasons why good people continue to follow bad leaders, and these neurological, psychological, and social phenomena are complex and powerful (and subject to exploitation by savvy operators and marketers).

In the end, we want leaders who add and multiply, not subtract and divide. We want leaders who get great results, with integrity, and sustainably. And we want leaders who create more followers and serve the larger good rather than themselves. We want leaders we admire, who make us better, and who call on our better angels.

Yes, we need better leaders, and we need them now. But most of all, we need to be our own best advocates and changemakers.

Tools for You

Related Articles

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, & TEDx speaker on personal development and leadership. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Crafting Your Life & Work online course or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!