Who are the people who fuel your passions—the things that consume you with palpable emotion over time? For me, there are so many.

There are five different types of such people:

- passion igniters

- passion inspirations

- passion pals

- passion partners

- passion enablers

(And read on to the end for one other important type…)

1. Passion Igniters

Your passion igniters are the people who set your passions ablaze in your life. Here are some examples:

For me, I fell in love with soccer in part due to a fiery and intense coach, John Goetz, who led our “Choppers” youth soccer team with gusto.

As the sweeper, I was the final line of defense before the goalie. If a long pass slipped through at half-field on a counterattack and their forward got behind me on a breakaway, I had a brief window to recover before my mark could take a shot. Sprinting at full speed to catch the opposing striker, I would always hear a booming call from Coach on the sidelines:

YEEEEEHAAAAAW!!!

You could hear it for miles. He knew I wouldn’t let the forward get a shot off.

That primal roar always sent a jolt coursing through me. I always found another gear when I heard it.

When I started learning to play the guitar, I had a hard time connecting with the lessons from my first music teacher. Eventually, I found a new teacher, Randy. He offered to teach me anything I wanted to learn. I’d bring him tapes and he’d show me how to rock out on all my favorite songs. That made all the difference. I was all in.

When I was in college, I discovered a passion for learning—and asking the big questions in life—thanks to brilliant teachers like Professor Roth and Professor Smith. Those fires are still burning in me, as bright as ever.

Alexandra, our oldest daughter, discovered a love for dancing when she joined a local dance group led by a talented and committed young dancer, Isabel. With her dance troupe, Isabel focused on spreading the joy of dancing and building community. They work with hundreds of dancers, from young children to young adults, and welcome them into Isabel’s giant and growing dance family. All the dancers perform on stage during their shows, with electrifying music, soaring choreography, and marvelous dancing. I’ll never forget when Alex had her breakthrough moment on stage. Isabel is a passion igniter.

Our other daughter, Anya, fell in love with animals, not just because she loves our own pets, but because her Mom grew up on a farm riding horses. Growing up, Anya spent a lot of time on the farm enjoying the countryside and the companionship of animals. Today, she’s considering a career working with animals.

My brother, Scott, loves to travel. If there’s a fun festival somewhere, anywhere, he’s game. He traces this back to all the postcards we got as children from our parents as they traveled around the world for our Dad’s business career. Scott was intrigued by all the foreign and exotic places. He lived in Japan for several years and now travels abroad often.

My friend, Christine, is a passion igniter for the young women rugby players she coaches, helping them not only discover a love of the game but also of strength and physicality.

Who are your passion igniters?

2. Passion Inspirations

Your passion inspirations are the people who made you feel that you wanted to explore or do something that you care about deeply. They breathed life into your passions through their example. In many cases, they’re famous.

I love to write. For me, Richard Bach, Paulo Coelho, Annie Dillard, Anna Quindlen, Fredrik Backman, Stephen R. Covey, Parker Palmer, Richard Leider, and Brene Brown have been passion inspirations over the years.

On the leadership front, my Dad was deeply inspired early in his career by Robert Greenleaf, a consultant and author who founded the modern servant leadership movement. It transformed my father’s whole approach to leading and sent him on a quest to find better ways to lead than the ones he experienced as an emerging leader.

If you’re committed to public service and social justice, your passion inspirations may be people like Mahatma Gandhi, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, Malala Yousafzai, or Alexei Navalny.

A budding entrepreneur? Maybe Steve Jobs, Richard Branson, Ratan Tata, Jack Ma, Oprah, Arianna Huffington, Lori Greiner, or Sara Blakeley inspire you.

For animals and the natural world, maybe it’s Jane Goodall or Sir David Attenborough.

And for acting and performing arts, maybe it’s Meryl Streep, Denzel Washington, Lin-Manuel Miranda, or Cynthia Erivo.

Who are your passion inspirations?

3. Passion Pals

Your passion pals are the friends you engage with on your passions, spending time together on the things that light you up.

For me in music, it was my band mates, with countless hours of practice in Patrick’s basement and Rob’s garage. These days, I geek out about books and podcasts with my friend Jamie and my Dad.

Do you have a workout buddy or hiking companion? A movie buff or gaming buddy? How about a foodie who samples new restaurants and dishes with you?

Who are your passion pals?

4. Passion Partners

Your passion partners are the people you collaborate with on passion projects, whether it’s a YouTube channel, photography, genealogy, pottery, or gardening. It can be romantic partners or business partners or both.

My friend Christopher Gergen and I were passion partners in writing a book, LIFE Entrepreneurs, together and building a company around it that helped people live with purpose and passion. In our research for the book, we interviewed 55 people who live intentionally and craft their lives around their passions, strengths, and values. In those interviews, we came across a wonderful surprise: many couples were helping each other do that.

For Paul, that mean supporting his new wife, Simi, as she launched a law firm and started a documentary project. And for Simi, it meant supporting Paul as he launched his new business. As Paul told me:

“This is so great. We’re helping each other with our dreams.”

For Linda and Roger, it meant co-founding a child-care company and launching and running humanitarian relief organizations in Asia and Africa. “For us it has been great,” recounted Linda. “We are extremely compatible. We have an enormous amount of respect for each other, and it adds this extra dimension to our relationship. It’s just incredibly rich to create an organization together.… Through all the very difficult start-up years, we had each other to lean on and celebrate our successes together.… It has really just worked.”

My Dad and I were passion partners on a book project about the kind of leadership it takes to build an organization that’s excellent, ethical, and enduring—what we called “triple crown leadership.” That work led to more writing as well as teaching and speaking together—a true joy.

Who are your passion partners?

5. Passion Enablers

Your passion enablers are the ones who give you the means or the opportunity to do the things you love.

For me, it begins with my Mom and Dad. I think back to all the times my Mom drove me to practices, games, lessons, and events. And the times she served as Class Mom or Team Mom or ran the Little League Snack Shack.

It’s also been my wife, Kristina, standing by me as I navigate my unconventional portfolio of work that includes writing, teaching, speaking, and coaching. And I supported her as she went back to school and changed careers, following her heart into work she loves and that she’s great at.

These passion enablers can include not only parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts, and uncles but also managers and colleagues.

Think about the marketing manager who notices that one of her team members loves designing social media graphics and visually rich campaigns but struggles with drafting content. The manager lines up training and small projects to foster this more specialized work.

Consider the astute boss who sees how passionate his direct report is about sustainability and conservation. The boss sponsors and mentors his employee in launching company service initiatives and sees how he not only lights up but also develops his planning, collaboration, and leadership skills.

Who are your passion enablers?

One More Type: Passion Killers

Unfortunately, there’s one more type: the passion killers. These are the folks who discourage you from pursuing your passions.

They insist you’re not qualified. That you’re not the sort of person who can lead that big project. They tell you how impractical it is and how you should wise up and play it safe. Often, they’re afraid you’ll struggle and fail if you take risks—or more concerned about how your choices reflect back on them. (This can lead you into the trap of living someone else’s life.)

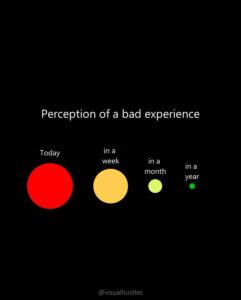

The voices of the passion killers tend to spawn the most insidious passion killer of all: self-doubt.

Self-doubt makes you question your capabilities and potential. It feeds on your uncertainty about yourself and your place in the world. It jumps all over you when you make a mistake or don’t reach a goal. It’s that voice in your head:

Don’t be a fool!

What if you make a mistake?

What will people think?

Conclusion

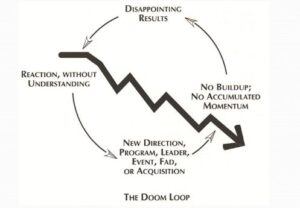

To some, passion sounds like pie-in-the-sky dreaming. Or unattainable. Part of the problem is due to fuzzy thinking. For instance: No, you probably don’t have just one passion. And no, everything won’t turn into butterflies and rainbows if you just “follow your passion.”

Passions are potent, especially when you pair them with your strengths. That gets you a big step closer to authentic alignment—when you’re being true to yourself and there’s a good fit between how you live and who you really are.

Passion is a critical component of this equation. Author Sir Ken Robinson calls it “the driver of achievement in all fields.” And Oprah Winfrey views it as energy, noting you can gain power by focusing on what excites you.

So, if you have people who have fueled your passion, be sure to reach out and thank them. And if you can play that role for others, I hope you step into it with gusto, realizing what a gift that can be.

If you have passion killers in your life, I hope you separate yourself from them—or at least draw healthy boundaries. Life is too short not to feel this amazing energy and see where it takes you.

Wishing you well with it. Let me know if I can help.

–Gregg

Reflection & Action Questions

- Do you have any passion igniters who have set your passions ablaze in your life?

- How about passion inspirations who have breathed life into your passions through their example?

- Do you have passion pals who you engage with on your passions?

- How about passion partners who you collaborate with on passion projects?

- Do you have passion enablers who give you the means or the opportunity to do the things you love doing?

- Have you thanked them? Why not reach out—today?

- How about passion killers who discourage you from pursuing your passions?

- What will you do about them?

Tools for You

- Traps Test (Common Traps of Living) to help you identify what’s getting in the way of your happiness and quality of life

- Quality of Life Assessment so you can discover your strongest areas and the areas that need work, then act accordingly

- Passions Probe to help you find the things that consume you with palpable emotion over time

Related Articles

- “The Power of Integrating Our Passions into Our Life and Work”

- “How to Discover Your Passions”

- “Why Self-Awareness Is So Important—And How to Develop It”

- “Tired of Settling? How to Set Your Life and Work on Fire”

- “The Trap of Self-Doubt—And How to Overcome It”

Postscript: Inspirations on Passions

- “Allow yourself to be silently guided by that which you love the most.” -Rumi, 13th century poet and Sufi mystic

- “The only way to do great work is to love what you do.” -Steve Jobs, co-founder, Apple

- “If there is any difference between you and me, it may simply be that I get up every day and have a chance to do what I love to do, every day. If you want to learn anything from me, this is the best advice I can give you.” -Warren Buffett, legendary investor

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, and TEDx speaker on personal development and leadership. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Best Articles or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!