Article Summary:

This article addresses best practices in goal-setting, including criteria for setting goals, a framework for evaluating a draft set of goals, and a goal-setting checklist. It’s the third article in a four-part series on goals.

+++

Goals are common in our life and work. But that doesn’t mean we’re good at setting and achieving them. Far from it.

How many goals have we missed over the years? For most people, it’s many. What’s going on?

Here we address what the research says about best practices in goal-setting and offer new criteria to use in goal-setting in two areas: first, in terms of setting individual goals and, second, in terms of evaluating a draft set of goals for quality and coherence.

In our previous articles in this series, we covered “The Benefits of Setting and Pursuing Goals” and “The Most Common Mistakes in Goal-Setting and Goal-Pursuit.” (Our focus is on individual goals—whether personal, professional, or otherwise—and not on goal-setting for teams or organizations, though much of what’s offered here applies in those cases too.)

First we take a quick look at existing goal-setting frameworks.

SMART Goals and Other Frameworks

There are different approaches to goal-setting in the literature and in practice. For example, researcher Edwin A. Locke identified five factors (clarity, challenge, commitment, feedback, and complexity), while University of Washington psychologist Frank L. Smoll identified three essential features of effective goal-setting (the “A-B-C of goals”: achievable, believable, and committed). In an MIT Sloan Management Review article, Donald Sull and Charles Sull recommend setting “FAST goals”: frequently discussed, ambitious, specific, and transparent.

The most famous formulation, of course, is “SMART goals,” developed by consultant George T. Doran, who proposed the SMART framework in a 1981 Management Review (AMA Forum) article. Here’s how Doran originally defined this approach:

- Specific: target a specific area for improvement.

- Measurable: quantify or at least suggest an indicator of progress.

- Assignable: specify who will do it. (Note that many people these days use “achievable” or “attainable” instead of “assignable.”)

- Realistic: state which results can realistically be achieved, given available resources. (Some people use “relevant” here.)

- Time-related: specify when the result(s) can be achieved. (Or “time-bound.”)

SMART goals are useful but insufficient. It’s a popular and memorable framework but missing several essential elements that are important for setting goals. Also, it doesn’t address how our goals may or may not hang well together. We address both facets of goal-setting in turn below.

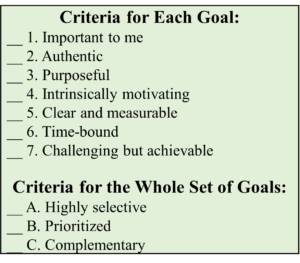

Criteria to Use in Setting Each Individual Goal

We begin with goal-setting criteria. Here are 7 criteria we should use in setting our individual goals:

1. Important to us

Set goals we can commit to wholeheartedly, knowing they’ll summon our dedication and resolve because they matter to us. We can even begin with the question: What’s most important to achieve now (or in the time period of our choosing, whether it’s the next quarter or year)?

2. Authentic

According to psychology researchers Ken Sheldon and Andrew Elliot, we’re happier, healthier, and more hard-working when we’re pursuing goals that are authentic to us and determined by us, not by others. In other words, our goals should be “self-concordant”: consistent with our core values and deeply held interests. A bonus: we experience bigger boosts in happiness when we achieve such goals. (1)

“The more that we choose our goals based on our values and principles,

the more we enter into a positive cycle of energy, success, and satisfaction.”

-Neil Farber, Canadian contemporary artist

3. Purposeful

We must be clear about the why behind our goals: Why do we want to achieve our goals? What benefits can we expect when we succeed? Ideally, our goals flow naturally from our personal purpose, core values, and vision of the good life.

4. Intrinsically motivating

Intrinsic motivation is the inner drive we have to do things out of our interest, enjoyment, or inherent satisfaction, rather than the desire for a reward (extrinsic motivation). According to researchers, intrinsic motivation is generally more potent than extrinsic motivation. When we work on things that are intrinsically motivating, it tends to involve us deeply and feel personally rewarding, pleasurable, and meaningful.

According to researcher Sonja Lyubomirsky in her book, The How of Happiness, “Numerous psychological studies have shown that across a variety of cultures, people whose primary life goals are intrinsically rewarding obtain more satisfaction and pleasure from their pursuits.” (2) Why? Such activities are enjoyable and inspiring to us, making us more likely to invest in and persevere and succeed at them. Also, they’re more likely to fulfill our core needs, such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness (see self-determination theory).

“If you want to be happy, set a goal that commands your thoughts, liberates your energy, and inspires your hopes.”

-Andrew Carnegie, Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist

5. Clear and measurable

A big problem with many goals is that they lack clarity and specificity. This dilutes the accountability factor. The clearer we are about what we seek to achieve, the more motivated we’ll be in our pursuit. And goals must be measurable. As the saying goes, we don’t get what we don’t measure.

6. Time-bound

If we don’t indicate the target date for accomplishment, we risk letting progress slip indefinitely and losing motivation. Effectively, our goals have no teeth. There’s no better motivator than a hard deadline.

7. Challenging but achievable

If a goal is too easy to achieve, it won’t inspire a sense of urgency and awaken the arousal systems in our brains. But we should avoid making a goal too arduous, because we’re unlikely to reach it if we don’t think we can. If we believe we might be able to achieve a difficult goal if we put in a lot of effort, that’s a good sign. (3)

It’s also good sometimes to have “stretch goals”—or what authors Jim Collins and Jerry Porras call “big, hairy, audacious goals” or “BHAGs.” These are goals that would really take our breath away if we were able to achieve them. But again, feasibility is important.

“Stretch goals can be crushing if people don’t believe they’re achievable.”

-John Doerr, Measure What Matters

Criteria for Assessing a Draft Set of Goals

There’s no shortage of criteria for individual goals out there, but it’s rare to see frameworks for how to assess a draft set of goals and whether they’re appropriate as a collection. Here are three criteria to use for that important analysis. The set of goals should be:

A. Highly selective

As we set goals, we must continually ask: Is this the right priority now? What’s the “opportunity cost”—the cost of the time and energy that could be spent in other pursuits? Ideally, we have only a few goals we’re focused on during a certain period—or a handful at most.

Psychologists note the problem of “goal competition” in which our goals can compete with one another for our time and attention. Essentially, the biggest barrier to one goal may be our other goals.

We tend to be too ambitious and set too many goals. By limiting our goals to the bare essentials, we help focus our energies. (See my article, “The Problem with Lack of Focus—And How to Fix It.”) When in doubt, reduce the number of goals. Less is more.

“We must realize—and act on the realization—that if we try to focus on everything, we focus on nothing.”

-John Doerr, Measure What Matters

B. Complementary

We must ensure that our chosen goals hang well together. We want them to add up to a powerful whole. And we should ensure that they don’t work at cross-purposes. Ideally, we look forward to our vision of the good life and think about what goals would move us in that direction.

C. Prioritized

We should arrange our goals in order of importance, from most important to least. Doing that will help us know which one to focus on if our goals end up competing for our time or resources.

Also, it’s extremely valuable to have total clarity about what our top-priority goal is. When people fail to achieve their goals, one common reason is overwhelm. There’s great power in having a singular focus—a rallying aim. There’s power in drawing a dividing line between what matters most and, well, everything else. If we don’t identify our top goal, we risk dilution and diffusion.

Goal-Setting Checklist

(See my online tool: Goal-Setting Template.)

Conclusion

Since we’re so accustomed to goal-setting, we may take it for granted and believe we’ve got it down. But if we had a true scorecard for all the goals we set, it would probably reveal a high percentage of abandoned or downgraded goals.

By using these 7 criteria for setting individual goals and 3 criteria for assessing our draft collection of goals, we can dramatically up our goals game.

Reflection Questions

- How are you doing in terms of these goal-setting criteria?

- What changes do you need to make in your goals?

Tools for You

- Goal-Setting Template to help you set goals you can achieve based on best practices

- Goals Guide: Best Practices in Setting and Pursuing Goals, a 30-page guidebook to walk you through this important process

- Traps Test (Common Traps of Living) to help you identify what’s getting in the way of your happiness and quality of life

- Quality of Life Assessment to help you discover your strongest areas and the areas that need work and then act accordingly

Related Articles and Resources

- “The Benefits of Setting and Pursuing Goals”

- “The Most Common Mistakes in Goal-Setting and Goal-Pursuit”

- “Goal-Pursuit: Best Practices“

- “The Problem with Lack of Focus—And How to Fix It”

- “Why You Should Do an Annual Life Review–And How“

- Huberman Lab Podcast, “Goals Toolkit: How to Set & Achieve Your Goals,” August 27, 2023

- John Doerr, “Why the Secret of Success Is Setting the Right Goals” TED talk

Appendix: OKRs

Many organizations nowadays use a management framework and goal-setting system called “Objectives and Key Results” (OKRs). This method was pioneered at Intel and is used by many organizations, including Alphabet/Google, Coursera, Disney, Exxon, the Gates Foundation, Intuit, MyFitnessPal, Nuna, and Remind (and many people, including Bono, the lead singer of U2, in his efforts to fight extreme poverty and preventable disease via the ONE Campaign).

In this OKR framework, the objectives are the concrete things we seek to achieve. In his book, Measure What Matters: How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs, legendary venture capitalist John Doerr recommends that objectives are “significant, concrete, action-oriented, and (ideally) inspirational.” He notes that they’re a “vaccine against fuzzy thinking—and fuzzy execution.”

The key results indicate how we can reach the chosen objectives. Doerr recommends ensuring that KRs are specific, time-bound, aggressive yet realistic, measurable, and verifiable.

Postscript: Inspirations on Setting Goals

- “The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.” -Michelangelo, Italian sculptor and painter

- “Shoot for the moon. Even if you miss it you will land among the stars.” -Les Brown, speaker and former member of the Ohio House of Representatives

References

(1) Sheldon, K.M., and Elliot, A.J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal Personality and Social Psychology, 76: 546-57.

(2) Also, according to a study of job satisfaction based on data from hundreds of workers, the ones who concentrated on intrinsic professional goals were significantly more satisfied with their jobs than those who didn’t. Source: Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Erez, A., & Locke, E. A. (2005). Core Self-Evaluations and Job and Life Satisfaction: The Role of Self-Concordance and Goal Attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 257–268.

(3) More than a thousand studies have shown that setting goals that are challenging and specific (versus easy and vague goals) is linked to increased motivation, persistence, and task performance. According to decades of research on goals by psychologist Edwin A. Locke, a pioneer in the field, setting goals improves performance. Also, hard-to-achieve goals improve performance more than easy-to-achieve goals, and having specific targets in our goals improves their effectiveness. Source: Edwin A. Locke, Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, Volume 3, Issue 2, 1968, 157-189.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, TEDx speaker, and coach on personal development and leadership. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto on living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Best Articles or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!