Our daily demands can be intense. We may have pressures and obligations at work. Household chores. Bills, taxes, mortgage payments.

On top of that, we want to help others: our spouse and children, our colleagues on a tough project, our friends and neighbors. Sometimes it can feel overwhelming—especially if we fall into the trap of focusing too much on others’ needs, draining our own reserves. Such excessive other-focus can get us into real trouble.

It’s a common challenge among people who work in the caring professions, including doctors, nurses, teachers, counselors, social workers, and veterinarians. Anyone who frequently cares for others or witnesses trauma is at risk of it, according to the American Psychological Association.

Also, many women struggle with this trap, perhaps because of all the societal expectations they encounter around caring, nurturing, and supporting households and families. Many women are raised to believe that being empathetic and compassionate is always appropriate—that it’s their duty.

Though this trap may be more common among women and those in the caring professions, it can affect anybody, and certain people are wired to be givers.

Empathy Overload and Compassion Fatigue

That brings us to the related problems of empathy overload and compassion fatigue. Empathy and compassion are related but there are also important differences between them.

Empathy is our ability to understand and share the feelings of another, while compassion is a feeling of sympathy and sorrow for someone facing misfortune, along with a desire to help.

Empathy overload, according to writer Dena Standley, feels like “your innermost personal world is continuously being invaded by the emotions and feelings of those around you.”

By contrast, compassion fatigue is emotional, psychological, and physical exhaustion from internalizing the suffering of others, leading to a reduced capacity to feel compassion for them. According to Dr. Charles R. Figley at Tulane University, “It’s like a dark cloud that hangs over your head, goes wherever you go and invades your thoughts.”

Both of these can be signs of what researcher Barbara Oakley calls “pathological altruism,” which she defines as “an unhealthy focus on others to the detriment of one’s own needs.” An important finding from the research on giver burnout is that it comes not from devoting too much time and energy to giving but rather from not being able to help people effectively despite all our efforts.

Signs of Being Too Focused on Others’ Needs

How to know if we’ve fallen into this trap? When we’re too focused on the needs of others and not enough on our own, we tend to:

- find it difficult to set healthy boundaries

- have a hard time saying “no” to people

- over-give to the point of exhaustion

- get so caught up in the feelings of others that we internalize them

- spend more time thinking about others’ feelings and needs than our own

- feel responsible for relieving the pain or suffering of others—or for fixing their problems and saving them

- lose ourselves in our relationships, becoming a passenger on their ship

- allow people to keep talking and talking, enabling their self-absorption or victim mentality

Part of what’s hard about this is that these behaviors of over-helping can become habitual, with our neural pathways wired to keep repeating those behaviors. Also, we all want to belong and be liked, but we get into trouble when this urge to belong and be loved overwhelms our urge to take care of ourselves.

The Problem with Being Too Focused on Others

When we’re too focused on others, we can:

- become blind to our own needs

- give so much to others that it harms our own health, relationships, or finances

- feel diminished energy

- lose our ability to concentrate

- have trouble making good decisions

- miss work

- become physically and emotionally exhausted, potentially leading to burnout

- experience emotional irritability, numbness, or emptiness

- withdraw from friends, family, and colleagues

- experience reduced empathic ability

- get pulled away from the things we need to do to pursue our purpose, vision, and goals

- end up resenting the people we’re helping

“Many of us find that we have squandered our own creative energies

by investing disproportionately in the lives, hopes, dreams, and plans of others.

Their lives have obscured and detoured our own.”

-Julia Cameron, The Artist’s Way

Sometimes focusing on other people’s problems is an escape from addressing our own problems. In some cases, over-helping is a way of covering up our own sense of unworthiness with an underlying belief that the person will reject or leave us if we don’t keep helping them.

According to behavioral experts, we can also become addicted to helping others. Our bodies activate serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin when we help others, creating a chemical cocktail that generates a “helper’s high.” With all these feel-good chemicals firing when we help people, it makes us want to repeat this behavior. This has obvious benefits as it encourages prosocial behaviors, but it can come with a cost for people whose actions become compulsive. It can also set a bad precedent in a relationship in which we unknowingly teach people to treat us as ones who are always there at their beck and call.

Too much sacrifice by one person can also harm a relationship by depriving it of appropriate levels of mutuality and reciprocity. Healthy relationships involve giving and receiving help from each other, and they’re not one-sided.

How to Avoid the Trap of Focusing Too Much on Others

So, what to do about it? Fortunately, there are many things we can do to address the trap of focusing too much on others’ needs. Here’s a punch list:

Recognize that sacrificing ourselves to help others is not sustainable. It will only lead to problems down the road.

Create separation and distance between ourselves and others when needed. If we struggle with over-helping, removing ourselves from these situations can be helpful.

Designate times for ourselves to enjoy life on our own terms without the press of outside needs and obligations. Go see a film, go for a walk, read a book. Choose things we enjoy and that restore us.

Get better at setting boundaries and saying no. State clearly that we can’t help right now. We’re all human, and we all have limits.

“It’s OK to do what is YOURS to do. Say what’s yours to say.

Care about what’s yours to care about.”

-Nadia Bolz-Weber, Lutheran minister

Develop a smart shield. Dr. Heidi Allespach, a psychologist at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine, urges medical residents to develop what she calls a “semi-permeable membrane” around their hearts. This advice is also good for anyone facing compassion fatigue. “Without enough of a shield, everything just comes in,” she explains. “And being overwhelmed with the feelings of others can feel like drowning.”

Reduce the magnitude of our helping. Recall that caring for someone doesn’t mean rescuing him or her. Recognize that even showing up in small ways can make a big difference. People can feel supported and nurtured even with small acts of kindness and connection. They may not want or need the full array of help. Sometimes just a visit, call, text, or meal can go a long way.

Recruit others in helping the person in need so we’re not alone. Having a community of helpers will probably lift the person’s spirits while also making our own burden more manageable.

Be clear about what we need from others and willing to ask for it even as we give to others. We must learn to advocate for ourselves as well as others we care about.

Employ “cognitive reappraisal”—reframing how we see a situation involving someone in need. For example, instead of believing the thought that the person will suffer without our help, think instead of plausible alternative scenarios, such as how the person can develop new coping skills that will serve them well going forward.

Imagine a friend of ours going through an episode of compassion fatigue like we’re experiencing (and its associated guilt for not being able to help more), and how we’d advise them to show themselves compassion and be sure to take care of themselves first.

“Our first and foremost task is faithfully to care for the inward fire

so that when it is really needed it can offer warmth and light to lost travelers.”

-Henri Nouwen, The Way of the Heart

Engage in self-care practices, including good nutrition, exercise, and sleep, relaxation, time in nature, breaks from our smartphones and newsfeeds, meditation, and/or journaling. Note that journaling can help us get out of our daily hustle and bustle and reconnect with our needs, emotions, and inner voice without the pressure of outside influences.

Work on guarding our hearts and keeping our emotional state from reaching extreme states such as empathy overload or compassion fatigue. Observe the emotions we feel when encountering the pain of others, letting the feelings flow through us and then leave, allowing us to be present and return to a state of ease.

Connect with family and friends. The research is clear on the powerful benefits of healthy relationships and how they contribute to our happiness and sense of fulfillment.

Recall that we have others who also depend on us and preserve our time and energy for them. If we’re too invested in helping one person in need, it can prevent us from supporting others such as our family or our team at work, or from doing other important work.

Conclusion

In sum, the answer isn’t forgetting about others and catering only to our own needs. Of course, we want to help people. Serving others is a key element of a good life. The key is striking a healthy balance and paying attention to others’ needs without sacrificing our own.

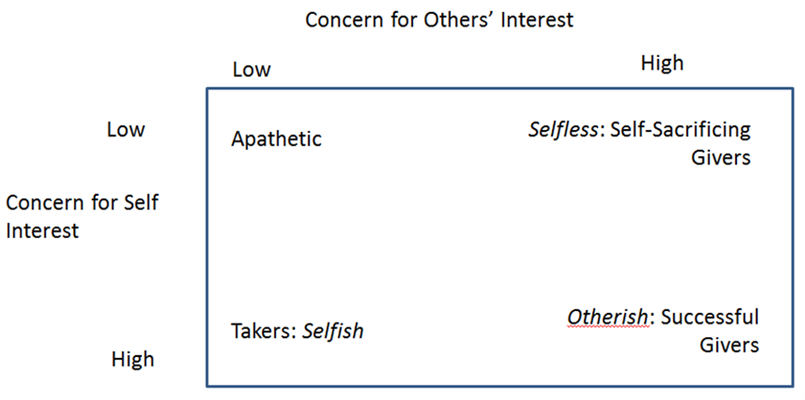

In his book, Give and Take, organizational psychologist Adam Grant plots different types of givers in a simple table, noting that the most successful givers are “otherish,” with high concern for self-interest as well as high concern for others’ interest, instead of being too focused on others or too focused on themselves. See the image below.

In the end, we need to take care of ourselves if we want to have the energy, stamina, and heart to keep helping others.

“Whatever we do to care for true self is, in the long run, a gift to the world.”

-Parker Palmer, A Hidden Wholeness

Tools for You

- Traps Test (Common Traps of Living) to help you identify what’s getting in the way of your happiness and quality of life

- Quality of Life Assessment to help you discover your strongest areas and the areas that need work and then act accordingly

- Crafting Your Life & Work online course to help you design your next chapter and create a life you love.

Related Articles and Books

- How to Avoid the Trap of Focusing Too Much on Others’ Needs

- The Trap of Losing Yourself

- The Trap of Caring Too Much About What Other People Think

- The Problem with Not Having Boundaries

- The Hidden Trap Catching Many High Achievers: Neediness

- The Problem with Neglecting Our Inner Life

- Good Nutrition for Health and Wellness

- Exercise and Movement for Health, Wellness, and Great Work

- Great Sleep for Health, Wellness, and Great Work

- Olga Kliemcki and Tania Singer, “Empathic Distress Fatigue Rather Than Compassion Fatigue?” in Pathological Altruism, ed. Barbara Oakley et al. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011)

- Richard Schultz et al., “Patient Suffering and Caregiver Compassion,” Gerontologist 47 (2007): 4-13

- Adam Grant, Give and Take (Viking, 2013)

Postscript: Quotations

- “Don’t lose yourself trying to be everything to everyone.” -Tony Gaskins

- “Take rest; a field that has rested gives a bountiful crop.” -Ovid, ancient Roman poet

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, and TEDx speaker on personal development and leadership. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Crafting Your Life & Work online course or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!