More isn’t always better.

Let that sink in.

More ≠ better.

Yet our brains fool us into thinking that it is. It’s an unconscious assumption, deep in our brains, that’s nearly impossible to shake.

It’s the idea that if we get more of the things we think we want, we’ll be happier.

But it’s a lie.

More what? More of pretty much everything: Success. Money. Status. Skills. Achievements. Victories. Conquests. Beauty. Followers. Honors. Devices. Shoes. Goals. Projects. More whatever. You name it. The disease or more.

We’re seduced by the possibility of the next thing. Seduced by the chase.

Here’s the thing: We accumulate them as we go, and then what?

We want more.

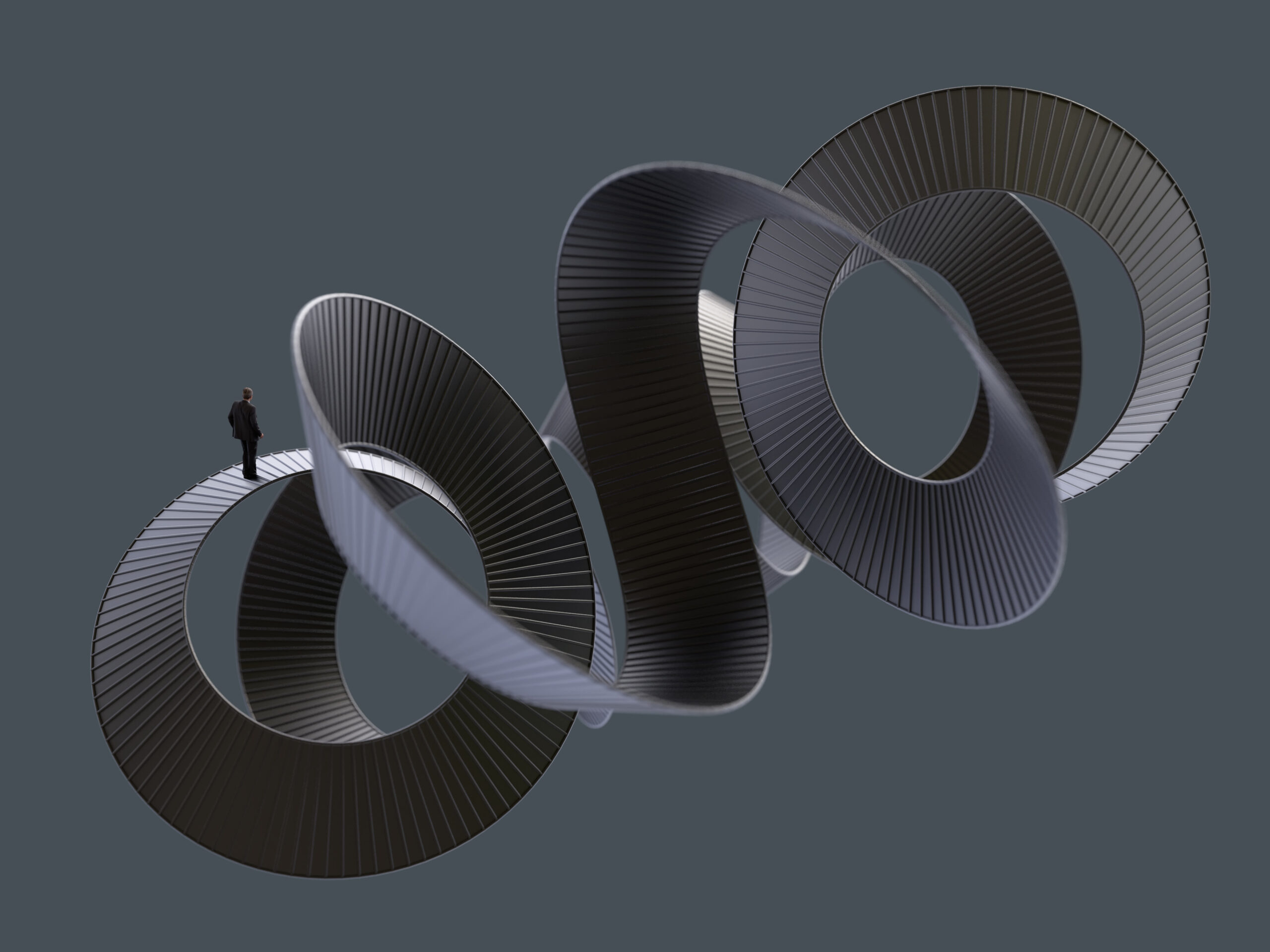

It’s like a black hole pulling ever-more things into its vortex. The ambition is never-ending. It can’t be sated—at least not the way we’re trying to sate it.

Yes, we get a temporary hit when we get something we want. The dopamine rush is real. But it’s fleeting. It’s never enough.

What’s Really Happening?

What’s going on here? How is it possible to want something, get it, and then not be happy?

One key driver is “hedonic adaptation”: we become rapidly accustomed to changes in our circumstances and then settle into that new baseline as if nothing had occurred.

What causes hedonic adaptation? According to researchers, it’s driven by a couple of things:

- Social comparison (if our neighbors get a nicer car, we feel inferior and feel a pang of envy and desire)

- Rising aspirations (if we get a big house, it’s not long before we want a bigger house)*

These dynamics lead to a “hedonic treadmill” in which, like a hamster, we run faster and faster to acquire more things but get nowhere in terms of increasing our happiness. It’s an absurd situation when viewed from a distance.

Wait, there’s more. What often happens is a clever redirect: our desire for more is a distraction, a way of avoiding emotional emptiness or relational distance or pain. Why sit and feel bad about these core foundations of true happiness when we can busy ourselves with yet another chase?

Also, we tend to focus on what’s missing, instead of appreciating what we have. Our evolutionary biology has caused us to focus much more on the negative than the positive. It’s called “negativity bias.”

Our Consumer Culture

Our consumer culture, which is excessively material and comparative, also drives our itch for more. It’s about acquiring and consuming things. It may generate corporate and advertising profits, but it doesn’t fill us up.

In this potent environment, we’re inundated with countless messages from others (e.g., family, friends, influencers, social media, ads) about what will make us happy.

The hard truth: there’s a big difference between what we think will make us happy and what actually makes us happy.

We tend to believe that we must pursue and find happiness, as if it’s “out there.” The logic is that happiness lies in changing our circumstances: “I’ll be happy when…” (…when I’m successful, when I get that promotion, etc.).

The Problem

The problem with this way of thinking and living–with the disease of more–is that it doesn’t work.

Getting more doesn’t fix the underlying problems. The pursuit of more, more, more—while it keeps us occupied and driven, like a rat sniffing cheese—will leave us less happy and fulfilled.

It can make us transactional, mercenary, and cynical. Our hearts harden. We feel accumulation anxiety, and we fill our days with need and busyness instead of love and grace.

“No matter how much value we produce today—whether it’s measured in dollars or sales or goods or widgets—it’s never enough. We run faster, stretch out our arms further, and stay at work longer and later. We’re so busy trying to keep up that we stop noticing we’re in a Sisyphean race we can never win.”

-Tony Schwartz, from The Way We’re Working Isn’t Working

That’s not to say that our pursuit of more is always bad. Sometimes we do need more. Sometimes getting more is good for us.

Far too many people on this planet and in this country live in poverty, or with economic uncertainty. They live in food deserts, or actual deserts. They lack access to clean water or basic health care, or stable employment or income-generating opportunities. Or they face violence or repression. In the face of such hardships, more security is a godsend.

The problem comes when people are financially secure and comfortable, but caught in a hollow cycle of need, greed, and speed. Caught in the disease of more.

Related Traps

This “disease of more” doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It operates alongside a number of related traps, including:

- Climbing mode: focusing so much on climbing the ladder of success, and on achievement and advancement, that we never take time for discovering who we are and what brings us joy and fulfillment

- Ego: being self-absorbed and caught up in our own stuff, without focusing on something larger than ourselves

- Emptiness: feeling empty about what we’re doing

- Materialism: getting too caught up in possessions and comfort while neglecting matters of the heart or spirit

- Outer-driven: being driven by the expectations of others

- Prestige: hunger for status, prestige, or approval

- The comparison game: constantly comparing ourselves to others and judging our worth by how we stack up on superficial metrics

- False metrics of success: measuring success in cold and calculating ways, such as income, net worth, position, or number of followers

Determinants of Happiness

Happiness is a slippery fish. It’s hard to pin down, but researchers believe there are a few major determinants of happiness.

First, we have a genetic set point of happiness. Researchers estimate that it comprises about 50% of our overall happiness.

Second, they estimate that about 40% of our happiness comes from intentional activity and our mindset.

Finally, they estimate that only about 10% of our happiness comes from our circumstances.

“Thus the key to happiness lies not in changing our genetic makeup (which is impossible) and not in changing our circumstances (i.e., seeking wealth or attractiveness or better colleagues, which is usually impractical), but in our daily intentional activities.” –Sonja Lyubomirsky, happiness researcher, author, and professor

What to Do

The mental tricks are deceptive, and the cultural conditioning powerful. What to do about it?

Here are several recommended practices based on research and experience:

First, stop the madness. Resolve to abandon the futile and endless pursuit of more, more, more. We can want happiness (who doesn’t?), but our obsessive chasing of it can backfire because it can lead to an epic ego trip—a narcissistic pursuit that leaves us wanting. Instead, connect with and contribute to others. Get over yourself.

Second, change the default viewpoint from comparison to contribution. Stop falling into the comparison trap and start asking how you can add value to those around you or to causes you care about.

Third, clarify your purpose and values—and live by them as best you can. Not perfectly, as that lies beyond our reach, but in a disciplined pursuit. This will help ensure that you don’t get waylaid, reaching the top of an ambition ladder only to find that it leaves you hollow or has taken you nowhere good, or at too great a cost (and quickly scouting for a new ladder).

Fourth, use your sword and shield. Once you know your purpose and values, use your metaphoric sword (your courage and will) to fight for them. And use your shield to defend against the bombardment of other people’s priorities and societal notions of success that don’t resonate with you besides the tingling of your “lizard brain.”

Fifth, live by your own lights and develop genuine self-worth, separate from your title, role, and possessions. Are you at risk of falling apart if you lose your current role?

Sixth, start simplifying your life by sloughing off the extraneous things that take up time, money, or space (e.g., clothes you never wear, the trinkets in your closet or garage that go untouched for years). Flip the equation from “more is better” to “less is more,” because less is light and free. “Less” has margin. “Less” frees you up to focus on what matters. See the “minimalism” and “essentialism” movements for great insights about how this works and how to start.

Finally, bring back a sense of gratitude for all you have, instead of resenting all the things you don’t have, or all you want or need. Having a gratitude practice can be powerful and effective in increasing our sense of wellbeing.

Note: You can’t do any of this without the presence of mind to lead yourself—to craft your life and work intentionally.

“Accomplishment. Money. Fame. Respect. Piles and piles of them will never make a person feel content. If you believe there is ever some point where you will feel like you’ve ‘made it,’ when you’ll finally be good, you are in for an unpleasant surprise. Or worse, a sort of Sisyphean torture where just as that feeling appears to be within reach, the goal is moved just a little bit farther up the mountain and out of reach. You will never feel okay by way of external accomplishments. Enough comes from the inside. It comes from stepping off the train. From seeing what you already have, what you’ve always had. If a person can do that, they are richer than any billionaire, more powerful than any sovereign.” -Ryan Holiday, Stillness Is the Key

Reflection Questions

- Do you have the “disease of more” in some parts of your life? How so?

- Which of the above practices resonate with you?

- What will you do, starting now?

Tools for You

- Traps Test (Common Traps of Living) to help you identify what’s getting in the way of your happiness and quality of life

- Quality of Life Assessment to help you discover your strongest areas and the areas that need work and then act accordingly

- Personal Values Exercise to help you clarify what’s most important to you

Related Articles

- Are We More Materialistic than We’d Like to Admit?

- Burnout and the Great Resignation

- Golden Handcuffs—Stuck in a Job You Don’t Like?

- Are You Trapped by Success?

- The Conformity Trap

- Is Your Identity Wrapped Up Too Much in Your Work

- Do You Have Margin in Your Life?

- The Trap of Caring Too Much about What Other People Think

- Feeling Behind? It May Be a Trap

- Choice Overload and Career Transitions

- The Comparison Trap

- Guard Your Heart

* On the flipside, sometimes there are benefits of hedonic adaptation, such as when our circumstances change for the worse, since we can also adapt to a new baseline after illness or tragedy.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, TEDx speaker, and coach on leadership and personal development. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for integrating our life and work with purpose, passion, and contribution) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Best Articles or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!