We humans are social animals. We’re wired to think about our role in the group and about how others think of us. It matters in our families, friendships, and work relationships. We can’t survive and thrive without tending to these relationships.

But there’s also a big trap here. The problem is when we’re so influenced by what others think—or, to be precise, what we think others will think—that it causes us to make choices that won’t serve us well over time. We avoid the short-term pain of a possible loss in status in exchange for the long-term loss of missing out on better things.

This dynamic can cause us to drift away from who we really are and what we really want to do. To drift toward the safety of what others expect. We can lose bits of ourselves as we seek approval from or try to please others.

These are common traps. And painful ones.

“The unhappiest people in this world are those who care the most about what other people think.”

-C. JoyBell C., writer

To be clear, it’s not that expectations are bad. We need expectations, and they can be helpful in many ways. The problem is becoming addicted to approval or fenced in by others’ expectations.

Haunted by Expectations

I see this again and again—and especially among young people early in their career. As they navigate through the dark and disorienting maze of career options, they feel haunted by the expectations of their parents—and of teachers, coaches, and peers: Be a doctor. Or lawyer. Or architect. Join the family business. Choose a profession. Go for salary and status. Climb the ladder. (Regardless of who you are, what you love, and what you long for.)

There’s a deceptive calculus at work here. The benefits of the approval flowing from those safe and respectable options can turn out to be shallow and fleeting. We can find ourselves in a career filled with things we don’t like—or even resent—and we’ve signed up for about 80,000 hours of it (the average amount of work people do today over a lifetime). So how does that bargain look now?

Meanwhile, there may be other costs: Paperwork. Time sheets. Bureaucracy. Boring meetings. Energy-sapping colleagues. Lousy bosses. All for what?

Is It a Good Fit for You?

Don’t get me wrong. There’s nothing wrong with being a doctor, lawyer, architect, or whatever, or with joining the family business, or pursuing a traditional career path IF—and here’s the rub—IF it’s a good fit for you. The key is that it’s your choice and that you’ve tried it and feel that it’s a good fit for you. That it fills you up with energy more often than it drains you.

Of course, not everyone has a choice. Sometimes we’re buried in debt or mired in financial stress and insecurity, or lacking better options. Many people face structural or institutional barriers or biases. But we usually have more choices than we think. It often comes down to our courage and agency, and to our imagination and hustle, despite the obstacles.

My sense is that we tend to overweight the external factors of approval and status early in life, while the intrinsic motivations quietly and steadily grow in importance as we grow older.

Avoiding this trap of getting pushed off course by the expectations winds is especially hard during transitions. Taking a step back to chart a new course summons potent fears of judgment and disappointment from others. But the reality may be that many are excited or even a bit envious about our new adventure (and most probably won’t even notice or think twice).

The Costs of Caring Too Much about What Others Think

When we’re in this mode of caring too much about what others think, we tend to:

- have a hard time communicating forthrightly when there’s disagreement or debate

- struggle with setting boundaries

- work too much and feel overwhelmed

- experience anxiety and stress

- feel resentment

- avoid doing things that call to us

- pass up on potential opportunities

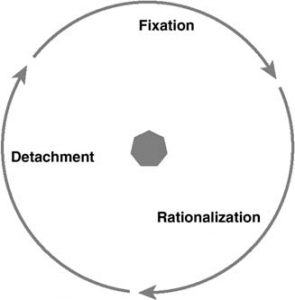

The need for achievement-based approval can become a compulsion. We become approval addicts looking for our next hit, and then the next. When does it end?

Life is too precious and short to let others determine our path.

It gets worse: The expectations of others are a terrible guide for deciding what’s right for us in our own particular context. Those expectations can be unrealistic, or even contradictory. What should we do with that? If we try to please everybody, we’ll fail miserably. No matter how hard we may try, we can never do things just as others might want or expect.

By surrendering to the Siren call of people-pleasing, we violate a silent sacred pact with ourselves, denying our nature and denigrating our integrity, leading to a downward spiral of self-doubt and inner turmoil.

Caring Too Much about What Others Think: Why Is This So Hard?

It’s easy to understand this problem conceptually, harder to self-diagnose because it’s emotionally charged and sometimes subconscious, but very difficult to address properly. Why?

For starters, we’ve been doing this for our whole lives—a tough habit to break. It’s been part of our conditioning as children—seeking the attention and approval of our parents and striving again and again to demonstrate our worth. When we did what others expected of us, we basked in soothing acceptance.

Our brains and bodies seek the chemical rewards of this stimulus-response feedback loop from our neurotransmitting hormones. This loop began in early childhood and it’s etched deep into our neural pathways. According to the late leadership expert Edward Morler, the stages of human development include moving from a focus on “Am I good enough?” in childhood to a healthier focus on “I am enough” in mature adulthood.

Related Traps to Caring Too Much about What Others Think

This excessive need for approval can also manifest in many related traps, including:

- getting too caught up in “climbing mode”

- constantly comparing ourselves to others and judging our worth by how we stack up

- conforming to societal conventions or conventional paths instead of blazing our own

- holding back or not trying due to fears about failure or threats to image

- feeling that others are racing ahead with more clarity or success while we lag behind

- sticking with a sub-optimal life or career path because we’re afraid of what others will think if we step off the treadmill and start over

- being short-sighted about what matters in life

- not setting proper boundaries or articulating needs because we want people to like us

- being consumed by a hunger for status, prestige, or approval

- pretending to be someone we’re not

- becoming addicted to work

How to Stop this Downward Spiral

Okay, so we know it’s a big problem. What to do about it? Here are 8 things we can do to stop this downward spiral:

- Acquire more self-awareness (in part by paying attention to our instincts and listening to our inner voice)

- Develop a clear and compelling personal purpose, values, and vision so that we’re clear about our deeper why, what’s most important to us, and what we want for our life

- Cultivate self-acceptance: Appreciate what we have and do well while shutting down our unrealistic inner critic

- Take time before saying yes to a new task or commitment and have clear and high standards for what we’ll spend time on

- Gain perspective: How much will what they think matter in a week, a month, a year, a decade? In the final analysis?

- Experiment with what it feels like to experience disapproval, sitting with it and getting a sense of how much it matters (if at all?)

- Notice how people may respect us for setting boundaries and for being clear and committed to our goals and aspirations

- Imagine and pursue the freedom and power on the other side of this mental block—the gift of finally letting ourselves be who we really are and long to become

“The most freeing experience of my life thus far has been to…

be unapologetically myself, and to stand in my own light.”

-Hannah Rose, therapist and writer

Reflection Questions

- Are you caring too much about what others think in some areas of your life?

- Which ones?

- Which action steps above will you start taking?

- Who can you turn to for help or accountability?

Tools for You

- Traps Test (Common Traps of Living) to help you identify what’s getting in the way of your happiness and quality of life

- Quality of Life Assessment so you can discover your strongest areas and the areas that need work, then act accordingly.

- Personal Values Exercise to help you clarify what’s most important to you

Related Articles

Postscript: Inspirations to Help You Avoid Caring Too Much about What Others Think

- “Being dependent on approval—so dependent that we barter away all our time, energy, and personal preferences to get it—ruins lives.” –Martha Beck, author

- “The first step toward change is to refuse to be deployed by others and to choose to deploy yourself.” -Warren Bennis, leadership author

- “I was driven by the expectation that I needed some type of profession. [I was also] driven by parental expectations and by looking at my peers.” -Warren Brown, entrepreneur

- “Everyone seems to have a clear idea of how other people should lead their lives, but none about his or her own.” –Paolo Coelho, Brazilian novelist

- “I was dying inside. I was so possessed by trying to make you love me for my achievements that I was actually creating this identity that was disconnected from myself. I wanted people to love me for the hologram I created of myself.” –Chip Conley, entrepreneur and author

- “You have to decide what your highest priorities are and have the courage—pleasantly, smilingly, nonapologetically—to say ’no’ to other things. And the way to do that is by having a bigger ‘yes’ burning inside.” –Stephen R. Covey, author

- “The problem comes when people are so eager to win the approval of others that they try to cover their shortcomings and sacrifice their authenticity to gain the respect and admiration of their associates.” –Bill George, leadership expert and author

- “Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.” -Steve Jobs, entrepreneur

- “Listen to your heart above all other voices.” -Martha Kagan

- “‘Finding yourself’ is not really how it works. You aren’t a ten-dollar bill in last winter’s coat pocket. You are also not lost. Your true self is right there, buried under cultural conditioning, other people’s opinions, and inaccurate conclusions you drew as a kid that became your beliefs about who you are. ‘Finding yourself’ is actually returning to yourself. An unlearning, an excavation, a remembering who you were before the world got its hands on you.” -Emily McDowell, writer and entrepreneur

- “So long as you’re still worried about what others think of you, you are owned by them. Only when you require no approval from outside yourself can you own yourself.” -Neale Donald Walsch, author

- “Most people are controlled by fear of what other people think. And fear of what, usually, their parents or their relatives are going to say about what they’re doing. A lot of people go through life like this, and they’re miserable. You want to be able to do what you want to do in life.” -Janet Wojcicki, professor, Univ. of California at San Francisco

“I do my thing and you do your thing. I am not in this world to live up to your expectations, And you are not in this world to live up to mine. You are you, and I am I, and if by chance we find each other, it’s beautiful. If not, it can’t be helped.”

-Fritz Perls, Gestalt Prayer

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, & TEDx speaker on personal development and leadership. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Best Articles or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!