Giving effective feedback is a powerful skill. When done well, it can be a big performance booster. When done poorly, a disaster bringing fear, discomfort, and resentment.

At its best, feedback is a great gift that can build trust and respect. At its worst, a spiral to anguish and despair. So tread carefully.

According to decades of research from Dr. John Hattie (2008), feedback is among the most powerful influences on levels of achievement.*

“We all need people who will give us feedback. That’s how we improve.”

-Bill Gates

Unfortunately, few people have learned how to give effective feedback or take the time to do it well, in part because of the fear associated with hurting feelings or damaging a relationship.

Through feedback you can provide information about how someone is doing on the way to reaching a goal. But it can also derail their learning, motivation, and performance if not handled well.

Feedback Is Not Advice

Note that feedback is not advice: “You need more examples in your report” is an example of advice, not feedback. Here are examples of feedback:

- (Golf coach to a golfer): “Each time you swung and missed, you raised your head as you swung so you didn’t really have your eye on the ball. On the one you hit hard, you kept your head down and saw the ball.”

- (Reader to a writer): “The first few paragraphs kept my full attention. The scene painted was vivid and interesting. But then the dialogue became hard to follow. As a reader, I was confused about who was talking, and the sequence was puzzling, so I became less engaged.” (Source: Grant Wiggins.)*

Best Practices for Giving Feedback

Here are some best practices for giving feedback:*

1. Private Setting: The place where you give feedback should be private and neutral. Make the recipient as comfortable as possible, and avoid whenever possible public scrutiny that will take focus off the issue at hand. In-person feedback is much better than written, because so many important nuances get lost in emails and text.

2. Mindset: Check your mindset to ensure that you come to the feedback session with a mindset of service, kindness, and openness, and that you’re presuming the best about the person (e.g., that they’re doing the best they can, or there may be obstacles that you don’t know about). Begin with a mindset of wanting the person to thrive and excel while feeling trusted and supported.

3. Positive Experience: Make it a positive experience for the recipient. The purpose of feedback is to help the person improve. Note that feedback should contain positive and negative information about how their actions are affecting their progress toward goals. Simple praise is not enough. Strive for a high ratio of positive to negative observations to ensure the response is not dejection and thus counterproductive. Be kind and considerate. Developing your emotional intelligence is essential.

4. Goal-Referenced: Indicate whether the person is on track toward goals or in need of a change. If the latter, brainstorm with them ways to get back on track.

5. Specific and Actionable: Help the recipient answer the question, “What specifically should I do more or less of next time?” (Thus, “You did that incorrectly” or “Good job” do not cut it.) The Center for Creative Leadership points to the “SBI method”:

- Situation: Describe the situation.

- Behavior: Describe the actual, observed behavior being discussed. Stick to the facts and avoid opinions and judgments.

- Impact: Describe the results of the behavior.

6. User-Friendly: Feedback must be accepted by the recipient to be helpful. View it from his/her perspective and present it clearly. Note the most important elements (not a long list of items without priorities).

7. Timely and Ongoing: The sooner the better, so the actions are fresh. Too many managers save feedback for performance reviews, which is way too late. Feedback should be frequent and ongoing.

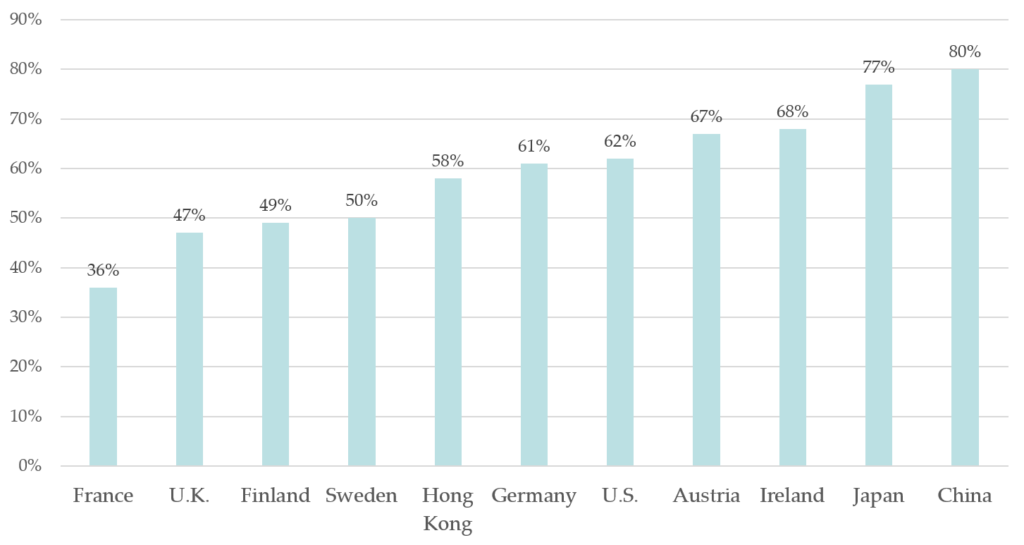

“A global study of over 1,000 organizations in more than 150 countries found that more than one-third of all employees had to wait more than three months to get feedback from their manager; nearly two-thirds wish they received more feedback from their colleagues.”

–James Kouzes and Barry Posner in The Leadership Challenge

8. Curious and Open: Invite their perspective and input. Search for mutual agreement and be open to their ideas. Ask them what ideas they have for moving forward. Ensure that they maintain a sense of accomplishment, competence, and agency.

9. Humble: Research has shown that people aren’t good raters of other people’s performance (or their own). We vastly overestimate our ability to do this well. (It’s called the “idiosyncratic rater effect.”) We assume we are clear and correct in our observations and judgments, but this is often much less true than we think.

Why Feedback Gets Derailed

To be effective at giving feedback, we must step back and understand why it is so difficult and dangerous. Think back to when you received feedback from a teacher in front of class, or from an intense and critical boss. Feedback gets derailed when:

- It focuses on the person and not the actions

- It comes across as one-sided, with the giver of feedback assuming they are right, they have all the relevant information, or they alone have the key to the only way forward

- It feels like an attack, not a gesture of solidarity and mutual commitment to improvement

Our Brains and Feedback

When dealing with feedback, we’re not just in the land of communication and leadership but also of psychology and neuroscience. Our brains are brilliant at discounting or rejecting feedback. Our egos get engaged. We get defensive. Or we deflect attention away from our flaws and mistakes. We focus on what we want to hear and block out what we don’t.

“When we give feedback, we notice that the receiver isn’t good at receiving it.

When we receive feedback, we notice that the giver isn’t good at giving it.”

-Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen in

Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well

We discredit or attack the one giving feedback, judging them extra harshly to protect our precious and wounded ego. Much of this is unconscious (an automatic triggering of our “fight or flight” response in sympathetic nervous system), so even harder for us to avoid (without strong self-awareness, emotional intelligence, and mindfulness practices).

The activation of this part of our brain reduces our ability to take in new information and impairs our learning, thereby defeating the very purpose of feedback. Professor Richard Boyatzis summarizes research noting that critical feedback engages strong negative emotion, which “inhibits access to existing neural circuits and invokes cognitive, emotional, and perceptual impairment.”*

The key is avoiding these negative triggers and taking care to engage more productive parts of the brain: the parasympathetic nervous system, associated with “a sense of well-being, better immune system functioning, and cognitive, emotional, and perceptual openness.” (Boyatzis)*

The way to do this is to notice what people did well, encourage them to reflect on and continue it, and add nuances or ideas to the understanding of the drivers of positive performance. Note what worked and ask the person what they were thinking or doing at the time. As Marcus Buckingham and Ashley Goodall say in “The Feedback Fallacy” in Harvard Business Review, “replay each small moment of excellence to your team.”

“As a leader, part of your job is to consistently let people know what they are doing well to reinforce those positive behaviors and to build emotional capital. Positive feedback makes work more enjoyable and more productive.” –Susan Scott, Fierce Conversations

The other problem is that some people walk around giving unsolicited advice. The assumption is that they’re right, others are wrong, others need correcting, and the act of doling out advice is like a gift from above. More often, though, it trounces on people’s feelings and makes things worse. People don’t want to be fixed. They want to feel supported and valued as they go through their own journey, including wins, losses, and learnings. We all want to be the heroes of our own story.

Receiving Feedback

Feedback is a two-way street. It must also be received well. That requires an ability to listen well: focusing intently on what the other person is saying (not using the time while they’re speaking to think through your counterpoints) and being open to their point of view (not getting defensive). When listening well, we ask questions, share our feelings, and summarize points while checking for accuracy and understanding. The conversation builds naturally as we go to new places together.

“Really pay attention to negative feedback and solicit it, particularly from friends.… Hardly anyone does that, and it’s incredibly helpful… Constantly seek criticism. A well thought out critique of whatever you’re doing is as valuable as gold.” -Elon Musk, entrepreneur

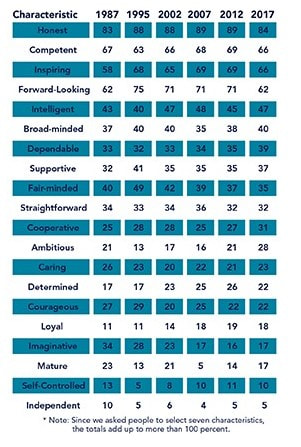

“On the Leadership Practices Inventory… the statement on which leaders consistently report engaging in least frequently is ‘asks for feedback on how my actions affect other people’s performance.’ Openness to feedback, especially negative feedback, is characteristic of the best learners.” -James Kouzes and Barry Posner in The Leadership Challenge

Giving and receiving feedback well is a communication superpower. Use it wisely.

Tools for You

Related Articles & Books

*Sources

- Leo Babauta, “How to Give Kind Criticism, And Avoid Being Critical,” Zen Habits, undated

- Ken Blanchard Companies, “Take the Fear Out of Feedback,” Perspectives, 2016

- Richard Boyatzis, “Neuroscience and Leadership: The Promise of Insights,” Ivey Business Journal, January / February 2011

- Marcus Buckingham and Ashley Goodall, “The Feedback Fallacy,” Harvard Business Review, March 2019

- Center for Creative Leadership, “Immediately Improve Your Talent Development with the SBI Feedback Model,” Leading Effectively articles, undated

- John Hattie, Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement (Routledge, 2008)

- Robert Nash and Naomi Winstone, “Why Even the Best Feedback Can Bring Out the Worst in Us,” BBC, March 8, 2017

- Grant Wiggins, “Seven Keys to Effective Feedback,” ASCD: Educational Leadership, September 2012

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, TEDx speaker, and coach on personal development and leadership. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Crafting Your Life & Work online course or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!