In the world of personal development, passion is one of the things that’s most misunderstood. “Follow your passion” is common advice.

But is it right?

The answer may surprise you.

What Is a Passion?

Our passions are the things that consume us with palpable emotion over time. They’re the things we love so much that we’re willing to suffer for them. Researchers have defined passions as strong inclinations toward activities we value and like or love, and in which we invest our time and energy. (1)

Author and coach Curt Rosengren calls passion “the energy that comes from bringing more of you into what you do. In essence, passion comes from being who you are.” Our passions are connected with our intrinsic motivation (our impulse to do something because of the inherent satisfaction of doing so and not the desire for a reward for it)—and with our innate talents and abilities.

Not Feeling Passion at Work

We can have passions in different domains of our lives. What are the signs of passion at work? The signs include loving our work, wanting to talk often about what we like about our work, or finding ourselves working extra hours even when we don’t have to, mainly for the inherent satisfaction.

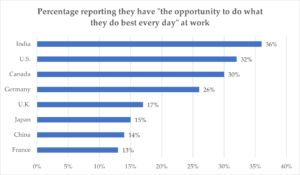

To what extent are people passionate about their work?

According to the data analysis team at Zippia, only 20% of U.S. workers are passionate about their job. Around the world, according to the 2013 State of the Global Workplace report by Gallup, only 13% of workers are passionate about their work.

The Benefits of Integrating Our Passions into Our Life and Work

There are powerful benefits to integrating passions into our life and work, according to researchers. For example, doing so can:

- boost our motivation and engagement

- increase our productivity and persistence

- enhance our focus and creativity

- help us achieve our goals

- motivate us to keep learning, growing, and developing in that area

- help us be more resilient in the face of challenges

- lead to more happiness and fulfillment

- help us avoid burnout

- lead to much higher job satisfaction, according to a meta-analysis that reviewed data from nearly a hundred different studies (2)

- lead to better work performance, according to a meta-analysis of sixty studies conducted over the past six decades

“Passion is the driver of achievement in all fields.”

-Sir Ken Robinson, author and advisor on education in the arts

Passion is also contagious. People pick up on our enthusiasm, and it can inspire them to find and work in their areas of passion as well.

There’s also a flip side to this: there’s much lost when we don’t have passion for what we’re doing. When we’re not living and working with passion, we’re much more likely to lack enthusiasm and “phone it in.” Over time, this can put us on a downward trajectory.

Confusion about Passion

Passion can be tricky because it often gets confused with other things, including hobbies and interests. Passion is related to these things, but there are important differences.

- A hobby is something we do for pleasure or relaxation and not as our main occupation.

- An interest is a feeling of wanting to be involved in something or to learn more about it, or something that attracts and holds our attention.

- A passion, as noted above, is something that consumes us with palpable emotion over time.

A key difference, then, between passions and hobbies and interests is the degree to which we’re emotionally invested in the activity. And this can change over time. A hobby can turn into a passion, and vice versa.

How to Know What Our Passions Are

To determine our passions, we can take assessments and/or observe our own experiences and ask ourselves questions like the following:

- What things bring me joy?

- Which subjects interest me the most, continually drawing me in?

- What would I keep doing enthusiastically even if I didn’t get paid for it?

- What am I continually curious about?

- What things do I get excited about doing or discovering?

- What fills me up with energy and makes me come alive?

- What activities do I lose myself in, losing track of time?

- What problem(s) do I feel compelled to solve?

- What am I curious about or fascinated with?

- Is there something I long to master?

- Is there a person, group, place, or cause that I feel compelled to help (e.g., youth, my hometown, endangered species, the planet)?

- What lit me up when I was a child?

We can also ask for feedback from others (e.g., family, friends, colleagues, mentors) about what they observe about our passions and how we can integrate them into our life and work.

Finally, we’re wise to experiment and explore possibilities—to try things.

Passion and Grit

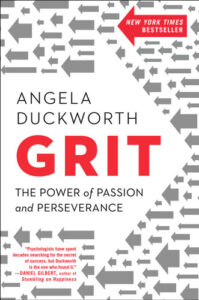

Angela Duckworth, University of Pennsylvania Professor and co-founder of the Character Lab, notes that a passion isn’t about just obsession. It’s also about consistency over time—about how steadily we work on certain things with sustained and enduring devotion.

In her book, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, she writes that a passion isn’t just something we care about and enjoy intrinsically, but something we care about “in an abiding, loyal, steady way.” She ties passion to what she calls “grit,” which is a combination of “passion and perseverance for very long-term goals.”

Passions Can Develop and Deepen over Time

Professor Duckworth notes that passions tend to be developed more than they’re discovered. In other words, there’s an important time dimension that tends to proceed with certain components, including interest, experimentation, discovery, development over time, practice, purpose, and persistence.

It begins, she notes, with interest—with intrinsically enjoying what we do. She notes that interests are typically “triggered by interactions with the outside world” and experimentation, and not discovered through introspection or analysis. Then, she writes, “what follows the initial discovery of an interest is a much lengthier and increasingly proactive period of interest development. Crucially, the initial triggering of a new interest must be followed by subsequent encounters that retrigger your attention—again and again and again.” In other words, the fire will go out if not tended to.

For the passion to blossom, it should be an activity that we practice—with “the daily discipline of trying to do things better than we did yesterday”—ideally leading to mastery.

For the passion to ripen, she reports, it should be connected to our purpose (our reason for being), with a conviction that our work matters. That means not only connecting to our personal interests but also to how we can serve or contribute to the wellbeing of others.

For us to maintain a passion, we must persevere with it through the inevitable challenges and setbacks.

In a nutshell, Duckworth recommends focusing not on following our passions but on fostering them intentionally and systematically over time.

“…here’s what science has to say: passion for your work is a little bit of discovery,

followed by a lot of development, and then a lifetime of deepening.”

-Angela Duckworth, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance

How to Integrate Our Passions into Our Life and Work

It’s one thing to know what our passions are (which isn’t straightforward for everyone), while it’s another thing to integrate them into our life and work.

For one thing, there are practical challenges. We live in the real world, with bills and mortgages to pay and retirements to save for. So, for starters, many people have given up on this game from the get-go. That’s understandable, but it warrants a second look.

Here are 8 steps we can take to integrate our passions into our life and work:

- Of course, we must begin by knowing what our passions are. (See above.)

- Challenge beliefs that aren’t serving us well. For example, reconsider a belief that that it’s not realistic to have passion in our life or to be passionate about what we do for a living.

- Evaluate how much time we’re operating in the area of our passions. Are we in the passion zone frequently, or rarely?

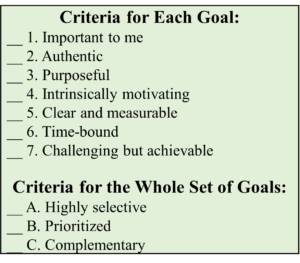

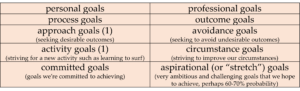

- Set goals that align with our passions. For example, if we have a passion for learning, we can set a goal of reading one nonfiction book every month or taking a new course every year.

- Decide what actions we’ll take and habits we’ll adopt to operate more in the areas of our passions. For example, we can choose one or two things that we do regularly as part of our morning, mid-day, or evening routine. Calendarize them and evaluate how it’s going regularly.

- Determine what we’ll do to reduce the amount of time we’re working on things outside our passions.

- Find others who share our passions and engage with them often.

- Connect our passions with our purpose, including ways we can serve others.

In this process, it may also be helpful to have a coach or mentor because we may not have clarity about our passions or how we can use them more.

As we go forward, we must remember to be patient. It can take a while to right the ship.

Myths and Misconceptions about Passions

There are many myths and misconceptions about passions. For starters, the idea that following our passion(s) will automatically lead us to success is prevalent and even a bit of a cliché.

It’s not wrong, but it’s only partly true.

It’s not enough to follow our passions. In this competitive world, our passions need a business model. We need to do things that others are willing to pay us for. And not all passions are well-suited to being our primary occupation that brings in our required income.

Many people don’t know what their passion is—and they may be intimidated by the thought. For many of us, our passions don’t come to us in a flash that’s crystal clear and that instantly changes our lives. Many of the people Angela Duckworth interviewed told her they spent years exploring several different interests, and the core passion wasn’t recognizable at the beginning.

In his book, Deep Work, Georgetown University computer science professor and author Cal Newport notes the flawed thinking that “there are some rarified jobs” that fuel passion—”perhaps working in a nonprofit or starting a software company—while all others are soulless and bland.” He argues that we don’t need a rarefied job; rather, what we need is a rarefied approach to our work. More on that below.

Some people may not want to have their passion incorporated into their job, as it may risk soiling it or leading to burnout. Also, we don’t necessarily have ONE PASSION. We can have many, and they can change over time.

There’s also a lot of confusion about the interplay between passion and purpose. For starters, many people use these terms interchangeably. Big mistake. A passion, as we’ve seen, is something that consumes us with palpable emotion over time. By contrast, our purpose is why we’re here, our reason for being. Stanford University professor William Damon defines it as “a stable and generalized intention to accomplish something that is at the same time meaningful to the self and consequential for the world beyond self.”

Ideally, we bring them closer together, tying our passions to our purpose and in the process redirecting our passions toward something more meaningful and significant.

“What ripens passion is the conviction that your work matters.

For most people, interest without purpose is nearly impossible to sustain for a lifetime.”

-Angela Duckworth, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance

Our passions, like pretty much anything in life, are at risk of dwindling over time. We can exhaust them or burn them out if we’re not careful. Two things can help here. The first is purpose. By connecting passions to purpose, we’ll attach them to a renewable source of energy. The second is novelty. Creatively finding new ways to use our passions—and with new people and different settings—will help keep the fire burning.

Mindsets about Passion

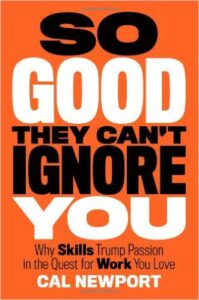

In his book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, Cal Newport points out that “When it comes to creating work you love, following your passion is not particularly useful advice.” He explains:

“The conventional wisdom on career success—follow your passion—is seriously flawed. It not only fails to describe how most people actually end up with compelling careers, but for many people it can actually make things worse: leading to chronic job shifting and unrelenting angst when one’s reality inevitably falls shorts of the dream.”

The idea here is that if we have unrealistic standards about what work will be like, we’re likely to become disappointed and perhaps even cynical. Part of the problem, Newport notes, is that we have this fantasy of a perfectly right dream job waiting for us out there. We only need to find it. This is often naïve. People may have a dream job for a while, but things have a tendency to change, with new managers, organizational transformations, industry shifts, and changes in our own lives. Great work is more of a mindset and pursuit than it is a destination.

Newport distinguishes between two different mindsets about work. The first is the “passion mindset.” The idea here is that if we do what we love, the world will make us succeed. This mindset (which is common) is focused on what the world can offer us. The problem: it’s too simplistic, and it’s misleading.

The second is the “craftsman mindset” (a craftsman is skilled at a certain trade, perhaps working skillfully with his or her hands to make things with exquisite attention to quality and detail). This mindset is focused on what we can offer the world, not on what the world will do for us.

Newport urges us to adopt the craftsman mindset, not the passion mindset—and get good at something. Really good. And really good at something via developing “rare and valuable skills.” With this mindset, we can build up “career capital,” which will give us a strong base for crafting a career of great work that’s also generous with freedom and autonomy, ideally tied to a compelling purpose.

Conclusion

In the end, it’s not so much about following our passions as it is about discovering, developing, and deepening them over time—and creatively integrating them into our life and work.

Ideally, we know not only our passions but also use our strengths (the things we’re good at, based on our innate talents, knowledge, and skills) to serve groups or causes we’re motivated to support in line with our core values. That’s a powerful approach to living honorably and living well.

Reflection Questions

- What are your passions?

- To what extent are you integrating your passions into your life and work (relationships, health, work, education, community, activities)?

- What more could you do?

- Is there anything preventing you from doing so and, if so, what will you do about it?

- What will you do differently, starting today?

Tools for You

Related Articles

Postscript: Inspirations on Passions

- “Allow yourself to be silently guided by that which you love the most.” -Rumi, 13th century poet and Sufi mystic

- “The only way to do great work is to love what you do.” -Steve Jobs, co-founder, Apple

- “If there is any difference between you and me, it may simply be that I get up every day and have a chance to do what I love to do, every day. If you want to learn anything from me, this is the best advice I can give you.” -Warren Buffett, legendary investor

- “Passion is energy. Feel the power that comes from focusing on what excites you.” -Oprah Winfrey, media entrepreneur, author, and philanthropist

- “One of the huge mistakes people make is that they try to force an interest on themselves. You don’t choose your passions; your passions choose you.” -Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO, Amazon

- “Paul and I, we never thought that we would make much money out of the thing. We just loved writing software.” -Bill Gates, co-founder, Microsoft

- “I did it for the buzz. I did it for the pure joy of the thing. And if you can do it for the joy, you can do it forever.” -Stephen King, writer

- “People who are connected to their passion can be spotted from a mile away.” -Mark Shearer, Executive Vice President, Pitney Bowes

(1) In the academic literature, researchers distinguish between “obsessive passions” and “harmonious passions” in what’s called the “dualistic model of passion.” With obsessive passions, we’re consumed with an activity and have a hard time letting it go. It can lead to conflicts between this activity and other important things in our life—and potentially injury, burnout, or other adverse consequences (e.g., when we keep dancing even when we’re injured). The problem occurs because we tie things like self-esteem or social acceptance to the activity, so we persist at it rigidly and develop uncontrollable urges to continue engaging in it.

With harmonious passions, by contrast, we freely accept the activity as important to us and engage in it willingly but don’t attach contingencies to it and don’t feel compelled to continue it. We’re able to leave space for other important things in our lives. Such passions lead to higher work satisfaction and don’t lead to those kinds of conflicts—or to burnout. Source: Vallerand, Robert & Paquet, Yvan & Philippe, Frederick & Charest, Julie. (2010). On the Role of Passion for Work in Burnout: A Process Model. Journal of personality. 78. 289-312.

(2) Mark Allen Morris, “A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Vocational Interest-Based Job Fit, and Its Relationship to Job Satisfaction, Performance, and Turnover,” PhD dissertation, University of Houston, 2003.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, TEDx speaker, and coach on personal development and leadership. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Best Articles or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!