Article Summary:

On the costs of social isolation and loneliness, the benefits of close relationships on our health, wellbeing, and happiness, and how to develop and maintain close relationships.

+++

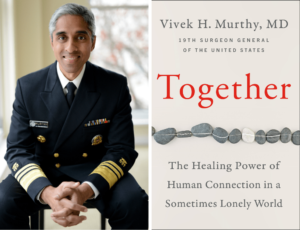

Loneliness and disconnection are big problems these days for many. This year, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy issued an advisory on the “public health crisis of loneliness, isolation, and lack of connection.” He noted, “Even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately half of U.S. adults reported experiencing measurable levels of loneliness.” According to a Guardian article, about 20 percent of people report that loneliness is a “major source of unhappiness in their lives.”

“Loneliness hangs over our culture today like a thick smog.”

-Johann Hari, Lost Connections

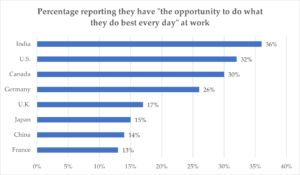

Workaholism and the dramatic increase of screen time in our lives both aggravate the problem. Average daily digital content consumption is now just under seven hours, according to a recent Forbes report.

If we want to address the issues, first we need to understand them clearly, so let’s begin by defining the relevant phenomena.

Defining the Problem(s)

There are several factors at work, from loneliness and social isolation to solitude.

In his book, Together: Why Social Connection Holds the Key to Better Health, Higher Performance, and Greater Happiness, Dr. Murthy defines loneliness as “the subjective feeling that you’re lacking the social connections you need.” He explains:

“It can feel like being stranded, abandoned, or cut off from the people with whom you belong—even if you’re surrounded by other people. What’s missing when you’re lonely is the feeling of closeness, trust, and the affection of genuine friends, loved ones, and community.”

Loneliness is a normal human emotion. We all experience it, but it can become problematic when we feel it too often. Researchers have identified several types of loneliness, including:

- intimate loneliness: when we feel we don’t have trust and a mutual bond with an intimate partner or close confidante.

- relational loneliness: when we feel we don’t have quality friendships and social support.

- collective loneliness: when we feel we don’t have a network or community of people who share our interests and values.

“These three dimensions together reflect the full range of high-quality social connections that humans need in order to thrive. The lack of relationships in any of these dimensions can make us lonely, which helps to explain why we may have a supportive marriage yet still feel lonely for friends and community.”

-Dr. Vivek H. Murthy, U.S. Surgeon General

Loneliness isn’t the same as social isolation. Researchers define social isolation as a lack of relationships with others and little to no social contact or support. Obviously, such social isolation often leads to feelings of loneliness.

Another related phenomenon is solitude. Some people conflate it with loneliness, but that’s a mistake. Researchers define solitude as a state of being alone and note that it can be voluntary or involuntary.

Solitude, it’s worth noting, can be positive. For example, it can help us have more time to reflect (a valuable thing when many of us lack margin in our lives) and lead to greater self-awareness. Also, solitude can help us develop authenticity and become more familiar with and comfortable being ourselves. Dr. Murthy points out that, perhaps surprisingly, solitude can help protect against loneliness.

The Costs of Loneliness and Disconnection

Loneliness and social isolation can have adverse consequences in our lives. According to a large meta-analytic review of the research literature over more than 30 years by Julianne Holt-Lunstad and her colleagues, “Actual and perceived social isolation” (i.e., living alone, having infrequent social contact, or having few ties with a social network) “are both associated with increased risk for early mortality.” (1)

According to researchers, loneliness and disconnection are associated with:

- a rise in cortisol (a stress hormone)

- increased blood pressure

- elevated blood sugar levels

- inflammation

- worse immune functioning

- poorer health behaviors (such as physical inactivity, worse sleep, and smoking)

- faster aging

- higher risk of heart disease, stroke, and dementia

- greater likelihood of premature mortality (1)

According to the Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, poor or insufficient connection come with a 29 percent increased risk of heart disease, 32 percent increased risk of stroke, and 50 percent increased risk of developing dementia among older adults. Also, lacking social connection can increase risk of premature death by more than 60 percent. (2) It can be just as deadly as certain diseases, according to researchers.

As if the physical health effects weren’t bad enough, loneliness and isolation often contribute to mental health challenges as well. For example, the risk of developing depression among adults who report feeling lonely often is more than double the risk among people who report feeing lonely rarely or never. When it comes to children, loneliness and social isolation elevate the risk of anxiety and depression both immediately and far into the future.

“Today it’s widely understood that one of the most important factors

in preventing and addressing toxic stress in children is healthy social connection.”

-Vivek H. Murthy, Together

Isolation can become a downward spiral, fostering discontent and shame, leading to further isolation. Many people have a tendency to go it alone through hard times and transitions, perhaps from their personality or upbringing. Unfortunately, that’s a recipe for more hardship.

“Protracted loneliness causes you to shut down socially, and to be more suspicious of any social contact…. You become hypervigilant. You start to be more likely to take offense where none was intended, and to be afraid of strangers. You start to be afraid of the very thing you need most…. disconnection spirals into more disconnection…. many depressed and anxious people receive less love, as they become harder to be around. Indeed, they receive judgment, and criticism, and this accelerates their retreat from the world. They snowball into an ever colder place.”

-Johann Hari, Lost Connections

The Benefits of Relationships

Forming and maintaining relationships, by contrast, comes with many benefits, according to researchers. British-Swiss journalist and author Johann Hari notes that just as bees evolved to be part of a hive, so we humans evolved to be part of a tribe. It stands to reason that there’s an evolutionary basis behind our urge to connect with others and form social bonds. Doing so helps us survive and reproduce, and it helps us access support in times of danger, distress, or trauma.

“…like food and air, we seem to need social relationships to thrive.”

-Ed Diener and Robert Biswas-Diener,

Happiness: Unlocking the Mysteries of Psychological Wealth

Social bonds are not just about surviving but also about belonging and thriving. Enter what psychologists call the “belongingness hypothesis”: that we have a “pervasive drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and significant interpersonal relationships.” (3) In a major review of the research literature on interpersonal attachments, researchers Roy F. Baumeister and Mark R. Leary found that our need to belong has two main features:

- first, we need frequent interactions with others that are positive or pleasant (or at least mostly free from conflict)

- second, we want interpersonal bonds that are stable and continuing and marked by genuine concern (and, ideally, mutual concern)

According to researchers, social relationships benefit our immune system as well as our cardiovascular and endocrine (hormone regulation) functions. (4)

Relationships and Happiness

Researchers have long tied the quality of our relationships to our wellbeing, happiness, and sense of fulfillment. The connection also shows up in surveys. According to a large 2023 Pew Research Center study, 61 percent of U.S. adults say that having close friends is extremely or very important in order for people to live a fulfilling life. (5)

The research on the link between social connections and happiness is extensive and powerful. (See the Appendix.)

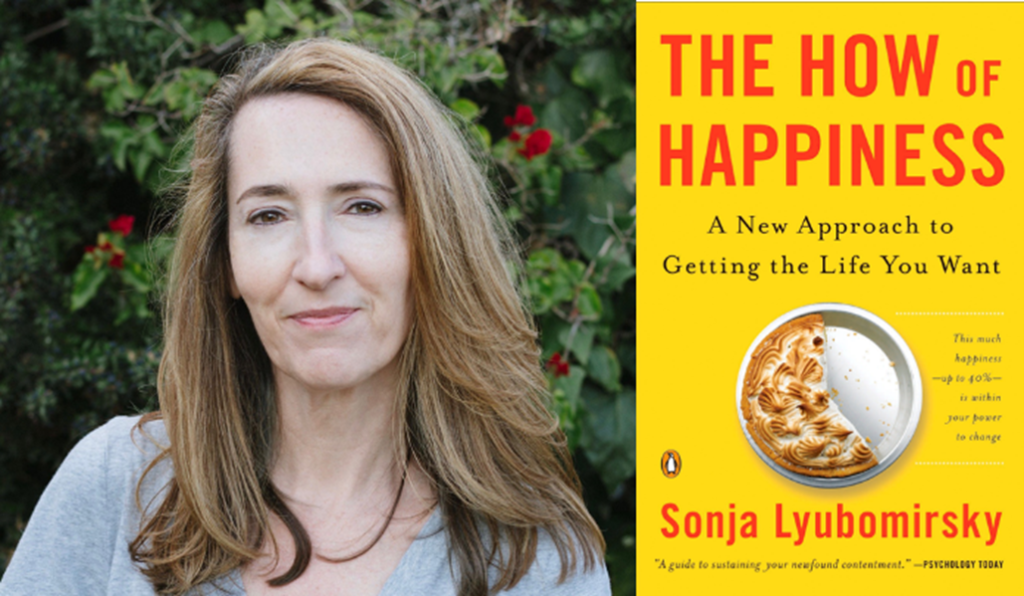

“The centrality of social connections to our health and well-being cannot be overstated…. One of the strongest findings in the literature on happiness is that happy people have better relationships than do their less happy peers. It’s no surprise, then, that investing in social relationships is a potent strategy on the path to becoming happier…. people with strong social support are healthier and live longer.”

-Sonja Lyubomirsky, The How of Happiness

According to Dr. Sonja Lyubomirsky, Distinguished Professor of Psychology at University of California Riverside, “The causal relationship between social relationships and happiness is clearly bidirectional.” In other words, when we improve our relationships, we’re likely to experience positive emotions. Then, our enhanced feelings of those positive emotions are likely to help us attract more relationships (and ones that are of high quality). That, in turn, will help make us even happier. She calls it “a continuous positive feedback loop” and “an upward spiral.”

The Dark Side of Relationships

Though the benefits are clear, we should also note that not all relationships are positive or beneficial. Far from it.

Many people are in relationships that are poor, manipulative, abusive, or even toxic. And good people sometimes have profound flaws that not only get themselves into trouble but also hurt others. Of course, all relationships go through ups and downs, and it’s not realistic to assume that they’ll induce happiness all the time. In fact, many people get themselves into trouble by expecting too much from their relationships, as opposed to doing the inner work of intentional improvement. Researchers have noted that relationships can be extremely stressful. (6)

How to Maintain Close Connections and Relationships

Since relationships are so important to physical and mental health and happiness, we’re wise to reflect on what we can do to nurture them. Here are things we can do to develop and maintain our relationships:

- Make time for important people in our lives and avoid the traps of perpetual busyness and workaholism that pull us away from them. Stop neglecting people and start cherishing them, starting with attention and quality time.

- Be honest, trustworthy, and reliable.

- Show interest in them.

- Open up and share our inner life, including our hopes, challenges, and fears, with close family and friends we trust.

- Demonstrate loyalty and commitment to family and friends.

- Support family, friends, and colleagues during their times of need.

- Show them we care with our actions as well as our words.

- Show them appreciation often.

- Express affection (e.g., holding hands, hugging, cuddling, massage). We humans are wired to need physical contact, and researchers have found a link between touch deprivation and many negative health outcomes, including anxiety, depression, and immune system disorders.

- Celebrate good news with them.

- Be polite and considerate.

- Listen more and better.

- Be positive—and don’t fall into the traps of complaining/muttering, catastrophizing, or having a victim mentality.

- Strive to understand their context, interests, and perspectives.

- Seek common ground and mutual interests.

- Treat them as they wish to be treated.

- Show understanding and empathy.

- Stop blaming others so much and take responsibility for our part in things.

- Respect their preferences and boundaries.

- Manage conflict well, including forthrightly and deftly raising concerns or disagreements instead of letting them fester.

- Avoid disrespect and contempt.

- Don’t hold grudges.

“You can’t stay in your corner of the Forest waiting for others to come to you. You have to go to them sometimes.”

-A.A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh

Conclusion

Our relationships with others are among the most precious gifts we can have in life. Too many people lose sight of that as they get lost in work, materialism, concerns or the day, or petty grievances.

One of the reasons that connections and relationships are so important in our lives—and such powerful contributors to our happiness—is that they get us out of our egoic shell. They get us to focus on others. It’s through our relationships that we can become better people by developing our empathy and compassion and giving part of ourselves to others.

Connect deeply and often. Do it gladly and urgently. You won’t regret it.

Reflection Questions

- Are you neglecting any important relationships in your life?

- Are you doing enough to develop new relationships?

- Are you doing enough to maintain your existing relationships that are important to you?

- What else will you do, starting today?

Tools for You

- Traps Test (Common Traps of Living) to help you identify what’s getting in the way of your happiness and quality of life

- Quality of Life Assessment to help you discover your strongest areas and the areas that need work and then act accordingly

- Crafting Your Life & Work online course to help you design your next chapter and create a life you love.

Related Articles

- “The Most Important Contributor to Happiness”

- “A Quick Relationship Checkup”

- “A Quick Family Relationship Checkup”

- “Check in on Your Friendships: A Quick Checkup”

- “How to Be More Present with People”

- “The Problem of Going It Alone”

- “Escaping the Trap of Our Ego”

- “Why Leaders Can’t Be Loners”

Related Books and Podcasts

- Vivek Murthy, Together: Why Social Connection Holds the Key to Better Health, Higher Performance, and Greater Happiness (Harper, 2020)

- Johann Hari, Lost Connections: Why You’re Depressed and How to Find Hope (Bloomsbury USA, 2018)

- “The Life-Changing Power of Connecting with Others,” episode 410, December 12, 2023 on the Feel Better Live More podcast with Dr. Rangan Chatterjee

Appendix: Research on Connections and Relationships

The research on the centrality of close relationships to our health, wellbeing, happiness, and fulfillment is extensive. Here are some important studies:

Harvard Study of Adult Development

The Harvard Study of Adult Development is a massive longitudinal study of hundreds of people for their entire adult lives. The study began in 1938 and is continuing to this day (after having multiple study directors) with its “Second Generation Study.” The study has evaluated mental and physical health and wellbeing, career enjoyment, retirement experience, and marital quality via interviews, questionnaires, medical exams, and psychological tests.

When asked what he’s learned from the study, Professor George Vaillant (a psychiatrist who led the study for decades) wrote: “Warmth of relationships throughout life have the greatest positive impact on ‘life satisfaction.’… (We now have) 70 years of evidence that our relationships with other people… matter more than anything else in the world…. Happiness is love. Full stop.”

Study of the Happiest People

In a study of 222 undergraduates, screened for high happiness using multiple confirming assessment filters, researchers sought to identify the characteristics of the happiest 10 percent of people among us. They found that the main distinguishing characteristic of the happiest people was the strength of their social relationships. (7)

“Here’s the most fundamental finding of happiness economics: the factors that most determine our happiness are social, not material…. social connectedness is the most important of all the variables which contribute to a sense of wellbeing in life.

And that is true at any age…. We are each other’s safety nets.”

-Jonathan Rauch, The Happiness Curve

World Values Survey

According to researchers who evaluated data from the World Values Survey, which surveyed people in more than 150 countries about their life satisfaction, the top factors that account for about three-fourths of reported well-being are: social support, generosity, trust, freedom, income per capita, and healthy life expectancy. (Note how many of these factors are social.)

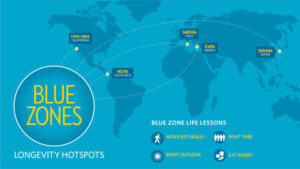

The Blue Zones

Dan Buettner, explorer, author, and American National Geographic Fellow, has written extensively about the “blue zones”: regions in the world where people live, or have recently lived, much longer than average, including many centenarians. The blue zones identified are: Okinawa Prefecture, Japan; Nuoro Province, Sardinia, Italy; the Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica; Icaria, Greece; and Loma Linda, California, U.S.

According to Buettner, there are common patterns of behavior across the blue zones, several of which concern relationships:

- “Belong”: belonging to and participating in a faith-based or spiritual community and attending services regularly.

- “Loved Ones First”: putting their families first, committing to a life partner, investing in their children with time and love, establishing and maintaining family and social rituals, and keeping aging parents and grandparents nearby or in the home

- “Right Tribe”: surrounding themselves with a tribe of people that they interact act with often and over their lifetimes (e.g., Okinawans created ”moais”–groups of five friends that committed to each other for life).

“The most successful centenarians we met in the Blue Zones put their families first. They tend to marry, have children, and build their lives around that core. Their lives were imbued with familial duty, ritual, and a certain emphasis on togetherness.”

-Dan Buettner, The Blue Zones

Postscript: Inspirations on Relationships and Connections

- “Union gives strength.” -Aesop, “The Bundle of Sticks,” 550 B.C.

- “Two are better than one, because they have a good reward for their toil. For if they fall, one will lift up his fellow. But woe to him who is alone when he falls and has not another to lift him up! Again, if two lie together, they keep warm, but how can one keep warm alone? And though a man might prevail against one who is alone, two will withstand him—a threefold cord is not quickly broken.” -Ecclesiastes 4:9–12 (English Standard Version)

- “The better part of one’s life consists of his friendships.” -Abraham Lincoln, lawyer, statesman, and U.S. president

- “Love is the only sane and satisfactory answer to the problem of human existence.” -Erich Fromm, German-American social psychologist, psychoanalyst, and sociologist

- “Call it a clan, call it a network, call it a tribe, call it a family. Whatever you call it, whoever you are, you need one. You need one because you are human.” -Jane Howard, Families

- “We all need to know that we matter and that we are loved…. While loneliness engenders despair and ever more isolation, togetherness raises optimism and creativity. When people feel they belong to one another, their lives are stronger, richer, and more joyful.” -Vivek H. Murthy, Together

- “There are two pillars of happiness… One is love. The other is finding a way of coping with life that does not push love away.” -George Vaillant, psychiatrist and Harvard Medical School professor, former director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development

- “Invest in friends. There is no other instrument that pays such high returns…. We need each other, but perversely we neglect each other. Every day we have an opportunity to exercise friendship, to make huge returns on a tiny investment, but foolishly we relapse into sleep and forgetting. Please take my advice to heart—forget bonds, forget stocks, forget gold—invest in friendship.” -Ronald Gottesman, USC professor

- “What often matters is not the quantity or frequency of social contact but the quality of our connections and how we feel about them.” -Vivek H. Murthy, Together

- “Isolation is fatal…. The burden of going it alone is heavy and limiting—and potentially dangerous…. In fact, social isolation can take up to seven years off of your life. Isolation contributes to heart disease and depression; it influences your immune system and leads to faster aging and advanced health problems.” -Richard Leider and Alan Webber, Life Reimagined

- “We believe that the most terrifying and destructive feeling that a person can experience is psychological isolation. This is not the same as being alone. It is a feeling that one is locked out of the possibility of human connection and of being powerless to change the situation. In the extreme, psychological isolation can lead to a sense of hopelessness and desperation. People will do almost anything to escape this combination of condemned isolation and powerlessness.” -Jean Baker Miller and Irene Stiver, Wellesley College

- “Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation has been an underappreciated public health crisis that has harmed individual and societal health. Our relationships are a source of healing and well-being hiding in plain sight—one that can help us live healthier, more fulfilled, and more productive lives.” -U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy

“For the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth—that Love is the ultimate and highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love.” -Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning (writing about an epiphany he had while in a concentration camp and thinking about his beloved wife, Tilly)

References

(1) Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237.

(2) Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community,” Washington, D.C., 2023.

(3) Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

(4) Umberson, D. & Montez, J.K. (2010). Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(Suppl), S54–S66.

(5) Kim Parker and Rachel Minken, “Public Has Mixed Views on the Modern American Family,” Pew Research Center, September 14, 2023.

(6) Walen, Heather R.; Lachman, Margie E. Social Support and Strain from Partner, Family, and Friends: Costs and Benefits for Men and Women in Adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2000; 17:5–30.

(7) Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very Happy People. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81-84.

+++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, TEDx speaker, and coach on personal development and leadership. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Crafting Your Life & Work online course or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!