One of the common traps of living affecting so many of us these days is overthinking—excessively analyzing something or dwelling on possibilities and second-guessing ourselves. We think about some things—mostly bad things—too much and for too long.

It can be mentally replaying awkward conversations or embarrassing moments repeatedly. That time we got dumped by our childhood crush. Or worrying about an upcoming presentation or interview. Putting off asking for a promotion or raise because we’re overthinking. Our thoughts spiral out of control when our boss mentions out of the blue that we need to talk.

I’ve fallen into this trap many times. I remember cringing repeatedly at my lame attempts to woo a girl in school that ended in flames of humiliation and self-flagellation. I recall jogging around a lake over and over again for months wondering if I should leave a job before finally stopping in my tracks and realizing that the prevalence of that question was a clear answer. Yet I struggled for months.

Overthinking is common. According to researcher Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, 73 percent of people aged 25 to 35 admitted to overthinking at some point in their lives. She also found that overthinking is more common among women than men, but common among both.

When author Jon Acuff and Dr. Michael C. Peasley of Middle Tennessee State University studied overthinking, they asked 10,000 people if they struggle with overthinking. The result? 99.5% of respondents said “yes.” What’s more 73% reported that it made them feel inadequate, and 52% noted that it left them feeling drained.

There are two prevalent forms of overthinking: ruminating and worrying.

Type 1: Rumination

One common form of overthinking is rumination, in which we engage in involuntary, compulsive thinking. We get stuck in negative thought loops and uncomfortable emotions.

Rumination tends to involve repetitive thinking about negative past events, problems, or concerns. With rumination, our thoughts can become so overwhelming and excessive that we can’t stop them.

It’s a dominant symptom of anxiety and depression, and it’s also habit-forming since we’re laying down neural pathways in our brains when we do it.

“This kind of compulsive thinking is actually an addiction. What characterizes an addiction?

Quite simply this: you no longer feel that you have the choice to stop. It seems stronger than you.”

-Eckhart Tolle, The Power of Now

Type 2: Worrying

Another common form of overthinking is worrying. When we’re worrying, we’re experiencing discomfort with uncertainty, leading to anxiety and stress. We’re constantly wondering, “What if…?”

Worrying involves fear and anxiety from anticipating that we may experience something negative or harmful. When we worry, sometimes we fixate on small details and lose sight of the big picture (such as a low probability of a bad event and a high probability that we’ll be able to deal with it just fine if it occurs).

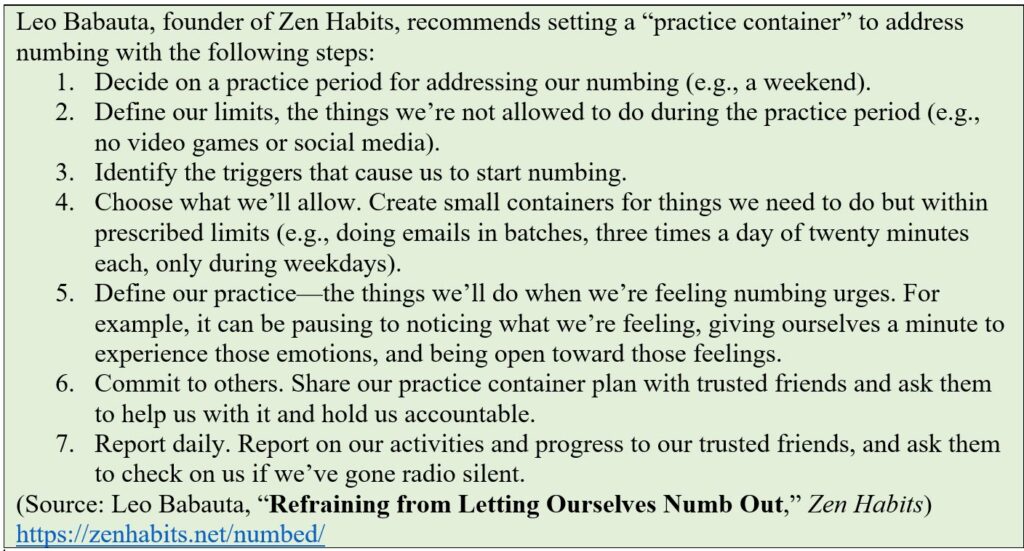

Sometimes worrying can take over, making us lose control of our thoughts. It can lead to procrastination, numbing ourselves via distractions, or excessively seeking constant reassurances from others.

“To think too much is a disease.”

-Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Signs of Overthinking

Beyond the examples of rumination and worrying noted above, overthinking can include the following:

- having trouble shutting off our thoughts at night (or other times)

- criticizing ourselves excessively for something we did in the recent past

- having so many thoughts and not knowing where to start

- cycling through possible scenarios in our minds

- fearing that we’re not enough and that others will judge us harshly or reject us

- frequently wondering what others are thinking of us

- assuming the worst and imagining terrible outcomes (i.e., catastrophizing)

- telling ourselves we can’t do things and bombarding ourselves with negative self-talk

- getting caught up in “analysis paralysis” and not moving forward on things

- fearing that we’ll never get better or that our situation won’t improve

Where It Comes From

Overthinking in all its forms, including rumination and worrying, comes from many sources. It can come from trying to control a situation, trying to get more clarity about what to do next, or trying to predict what will happen to reduce our anxiety. A common underlying theme is discomfort with uncertainty.

Those who are motivated by achievement, prestige, or perfectionism can be more prone to overthinking. According to neuroscientist Sanam Hafeez, “Perfectionists and overachievers have tendencies to overthink because the fear of failing and the need to be perfect take over, which leads to replaying or criticizing decisions and mistakes.”

Overthinking can also be a habit picked up from our childhood—something we learned from having to deal with tough situations such as over-controlling parents. It can come from trying to reduce feelings of helplessness or grasping for comfort. We convince ourselves that there may be a solution to the problem if only we keep thinking it through.

In addition, overthinking can come from urges to procrastinate or avoid decisions. In essence, we’re convincing ourselves that we can’t make a decision because we haven’t analyzed it enough yet, and that allows us to avoid blame for being wrong.

Finally, it can come from stresses or trauma, which causes our brains to get stuck in a state of hyper-vigilance as a defense mechanism.

Overthinking and Leaders

Overthinking can be a big problem for leaders. Many leaders must make hundreds of decisions a day, a stressful burden. Some leaders can get lost in deliberation so much that it inhibits decision-making and necessary action.

In her book, Trust Yourself, Melody Wilding talks about “sensitive strivers,” high achievers who think and feel more deeply. Studies show, she notes, that they have more active brain circuitry and chemicals in neural areas related to mental processing, and that they comprise about 15-20% of the population.

How do followers respond to leaders who overthink? Summarizing research from the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Professor Zakary Tormala noted that “people seem to be less drawn to and less open to being influenced by individuals who overthink small decisions or ‘underthink’ big ones.” What people want, according to the researchers, is an appropriate level of “thought calibration” that adjusts the level of thinking to the significance of the decision at hand.

The Problem with Overthinking

Unfortunately, overthinking and its manifestations can get us into trouble in many areas. For example, it can:

- lead to mental fatigue and burnout and make us feel drained

- elevate our stress levels

- disturb our sleep

- harm our health, potentially including suppressed immune functioning and increased incidence of coronary problems, according to medical professionals

- increase our risk of mental health problems, substance abuse, or suicide

- lead to avoidance

- impede our ability to make decisions

- lead to inaction

- cloud our judgment

- waste our time

- reduce our productivity

- interfere with our problem-solving, since we end up dwelling on problems instead of solving them

“If there is no solution to the problem then don’t waste time worrying about it.

If there is a solution to the problem then don’t waste time worrying about it.”

-Dalai Lama

- crowd out our heart, intuition, and inner wisdom, as we overindulge in cerebral thinking and analysis

- inhibit our creativity

- harm our relationships by driving people away, causing new problems like loneliness or isolation

- sap our sense of agency and control in our lives

- prevent us from achieving our dreams

In the end, our overthinking gets us nowhere, because our mind keeps coming up with new questions and concerns. Often, we’re overthinking about things that we have no control over, a true waste of time and energy. And we’re imagining worst-case scenarios that rarely come to fruition.

“We suffer more often in imagination than in reality.”

-Seneca, ancient Roman philosopher

We tend to engage in negative thoughts when we’re overthinking, not positive ones. Researchers have found that we have a negativity bias, a tendency to register negative stimuli more readily and to dwell on them. As humans, we weight negative events more heavily than positive ones.

“We ruminate on suffering, regret, and sorrow. We chew on them, swallow them, bring them back up,

and eat them again and again. If we’re feeding our suffering while we’re walking, working, eating, or talking,

we are making ourselves victims of the ghosts of the past,

of the future, or our worries in the present. We’re not living our lives.”

-Thich Nhat Hanh, Vietnamese Buddhist monk, peace activist, author, and teacher

What to Do About Overthinking

Fortunately, there are many things we can do to address our overthinking. Below are dozens of simple practices from which we can choose.

Catch ourselves in the act of overthinking. If we can bring this mischievous habit into our awareness, then we can begin reprogramming our brains with more enjoyable and productive ways of thinking. Author Melody Wilding recommends using a pattern interruption technique such as silently saying “stop” when we start overthinking, visualizing our worries floating away, or flicking a rubber band on our wrist when we catch ourselves overthinking.

Recognize that a key to success in life is taking more action more often. One of the biggest mistakes we make in our lives is having a thought-to-action ratio that’s way off kilter and top-heavy toward thought, weighing us down in anxiety and inaction. Change our focus from problems and worries to solutions and actions.

“The antidote to overthinking isn’t more thinking—the antidote is action.

You don’t think your way out of overthinking. You act your way out.”

–Jon Acuff, Soundtracks

Decide to become a person of action instead of an overthinker. Enjoy getting lost in doing things. Try it for a while and note the differences across domains of our lives, from energy and momentum to confidence and results.

Recognize that our thoughts are like a dial, not a switch. This insight from David Thomas, author and Director of Family Counseling at Daystar in Nashville, teaches us that we can’t switch off our thoughts, but we can turn the volume down on rumination and negative thoughts—especially via actions.

Practice making quick decisions. Start with small things and count down from three: “three, two, one… choose.” Then go with it. Get used to a faster decision cycle and note the results. Develop decision processes and criteria, such as prioritizing our core values when making important decisions.

Determine what’s creating fear in us. Get better at recognizing how many of our fears are false phantoms, much like the childhood monsters we feared lurking under our beds. And get better at overcoming our fears.

Focus intensely on something. Listen to music and focus intently on something in it, like the lyrics or the guitar line. Or study a drawing or painting and examine the shapes, lines, colors, and proportions.

Learn what our overthinking triggers are and avoid them. They could be certain social media accounts, news sites, or sticky situations with certain people.

Give ourselves a time budget for how long we’re allowed to think about something. Then choose to move on after that. Our overactive minds may be satisfied with a fixed allotment of thinking time. (Some people call this “worry time” and report that it’s comforting to them.)

Develop our confidence and learn to trust ourselves more. Learn to trust that things will probably be okay and work to overcome any instances of “impostor syndrome.”

Determine the things that we do have control over and focus on them. If we’re worried about an important upcoming meeting, we can do a great job preparing for the meeting and then make sure we get a good night’s rest and arrive early to set up. Then we can be satisfied that we’ve done our job.

Get better at letting things go. Recognize that we’re probably placing way more weight on things than the situation warrants. While we may be beating ourselves up over a situation, it’s likely that others hardly noticed our part in it or just moved on. People think way less of us than we imagine.

Change our thoughts into questions. For example, we can shift a thought from “I can’t believe I said that” to “What could I say differently next time?” We can change a thought from “I don’t have close friends” to “What should I do to be a better friend?”

Get some exercise. This leads to the removal of stress hormones and comes with so many benefits, including better brain health, greater muscle and bone strength, reduction in the incidence of disease, better mood, greater energy levels, and more.

Get out into nature. Our brains become calmer and sharper after we spend time in nature, according to researchers. We can hike in the woods or do some gardening, giving our minds a chance to enjoy the break and focus on pleasant sights and activities.

Try relaxation techniques. Examples include taking deep breaths or doing yoga. The research is clear that such simple acts can dial down the mental noise in our heads.

Do things that interest us and that occupy our attention. Engage in fun activities and hobbies. These can bring relaxation, contentment, and satisfaction into our lives and reduce our stress—and even better if we do them with others.

Connect to our senses. Try the “54321 grounding method,” in which we take deep breaths and become aware of our surroundings and then look for five things we can see, four things we can touch, three things we can hear, two things we can smell, and one thing we can taste. Simple exercises like this can help stop the drumbeat of our thoughts.

Journal. It’s cathartic to write our thoughts down. Writing our thoughts down can stop us from ruminating. It can restore a sense of control as we gain insights and discern patterns. Journaling doesn’t have to be formal or structured. We can do a simple brain dump and just write down our thoughts as they arise.

Help others with small acts of service or simple acts of kindness. This is a great way to add more meaning and connection in our lives while also getting us out of our own heads.

Lean into positive relationships. By being with others, we can engage and connect, have fun, support each other, and silence our mental gremlins.

Replay happy memories. Instead of feeding into worries or concerns, relive good times and happy memories. Talk with an old friend or flip through a cherished photo album.

Find sanctuary. These are places or practices of peace that reconnect us with our heart. (See our article, “Renewing Yourself Amidst the Chaos.”)

Go out on adventures. Adventure makes us feel more fully awake, alive, and free. It fuels us with the energy and excitement of exploration. And it takes our minds off the mundane. It’s hard to ruminate when we’re climbing a mountain or trekking in new areas. (See my article, “Why We Want Adventure in Our Lives—And How to Get It.”)

Bring awe back into our lives. Awe is a powerful emotion and a marker for life at its grandest. It gives us an experience of vastness and mystery. How much can we worry when we’re gazing at the cosmos, studying the intricacies of a spider web, or experiencing a great performance? (See my article, “The Power of Awe in Our Lives.”)

Engage in prayer, worship, or spiritual contemplation. By doing so, we can rise above the immediate concerns of our overactive mind and tap into something larger than ourselves with reverence, gratitude, and wonder.

Meditate. According to researchers, meditation can calm our sympathetic nervous system and decrease our anxiety, stress, and emotional reactivity. Meanwhile, it can help with our focus and overall well-being.

“If you want to conquer overthinking, bring your mind to the

present moment and reconnect it with the immediate world.”

-Amit Ray, Meditation: Insights and Inspirations

Talk to a friend—or a professional therapist or counselor. Part of the value here is getting things off our chest, which can reduce our propensity to keep thinking about them, not to mention learning new coping skills.

Clearly, there are many things we can do to address our overthinking. The point isn’t that we must do all of them. We should experiment with the ones that are instinctively most appealing and determine which ones work the best for us.

Let’s also note here what doesn’t work in trying to overcome overthinking. We know from research that we can’t just tell ourselves not to have certain thoughts. That can lead to more thoughts on the subject at hand. For example, if we’re told not to think of a pink elephant, our brains will do the opposite and think about it. Instead, we need to replace negative thoughts with different and better ones.

Conclusion

These days, we ask a lot of our minds. We shock them with breaking news alerts and crises around the world. We feed them with email, social media, digital entertainment, and all manner of stimuli.

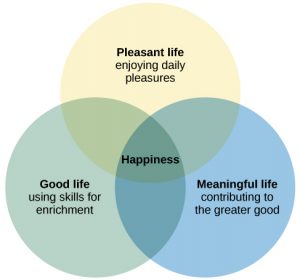

If the quality of our lives is influenced deeply by the quality of our thoughts, isn’t it worth addressing our negative thinking patterns like overthinking, rumination, and worrying? How much more peace, joy, and impact might we have if we were to restore a healthier balance between our head and our heart?

Reflection Questions

- To what extent are you struggling with overthinking, rumination, or worrying?

- How is it affecting your mental health, well-being, performance, and happiness?

- What will you do to tame your overthinking dragons?

Tools for You

Related Articles

- “The Mental Prisons We Build for Ourselves”

- “How to Stop Catastrophizing—Managing Our Minds”

- “Why Monkey Mind Is Worse Than You Think”

- “17 Signs Your Monkey Mind Is Running Wild”

- “How to Practice Acceptance When Things Are Tough”

- “How to Be More Decisive in Your Life and Leadership”

- “What Are You Avoiding?”

- “The Incredible Benefits of Being Action-Oriented”

- “The Perfectionism Trap—And How to Escape It”

- “The Trap of Not Being Grateful for What We Have”

- Melody Wilding, “How to Stop Overthinking Everything,” Harvard Business Review, February 10, 2021.

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504.

- Pillai, V., & Drake, C. L. (2015). Sleep and repetitive thought: the role of rumination and worry in sleep disturbance. Sleep and Affect, 201-225.

Related Books

- Jon Acuff, Soundtracks: The Surprising Solution to Overthinking

- Eckart Tolle, The Power of Now

- Melody Wilding, Trust Yourself: Stop Overthinking and Channel Your Emotions for Success at Work

- Jennie Allen, Get Out of Your Head: Stopping the Spiral of Toxic Thoughts

- Nick Trenton, Stop Overthinking: 23 Techniques to Relieve Stress, Stop Negative Spirals, Declutter Your Mind, and Focus on the Present

- Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, Women Who Think Too Much

Postscript: Inspirations on Avoiding Overthinking

- “While you were overthinking, you missed everything worth feeling.” -Nitya Prakash

- “Overthinking steals time, creativity, and productivity by making you listen to broken soundtracks. Do you know what happens when you listen to new ones? You give your dreams more time, creativity, and productivity.” -Jon Acuff, Soundtracks

- “Inaction breeds doubt and fear. Action breeds confidence and courage. If you want to conquer fear, do not sit home and think about it. Go out and get busy.” -Dale Carnegie

- “Good days start with good thoughts.” -Jon Acuff, Soundtracks

“A crowded mind

Leaves no space

For a peaceful heart.”

-Christine Evangelou, writer

Appendix: Support Resources

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Gregg Vanourek is a writer, teacher, & TEDx speaker on personal development and leadership excellence. He is co-author of three books, including LIFE Entrepreneurs: Ordinary People Creating Extraordinary Lives (a manifesto for living with purpose and passion) and Triple Crown Leadership: Building Excellent, Ethical, and Enduring Organizations (a winner of the International Book Awards). Check out his Crafting Your Life & Work online course or get his monthly newsletter. If you found value in this article, please forward it to a friend. Every little bit helps!